oleebook.com

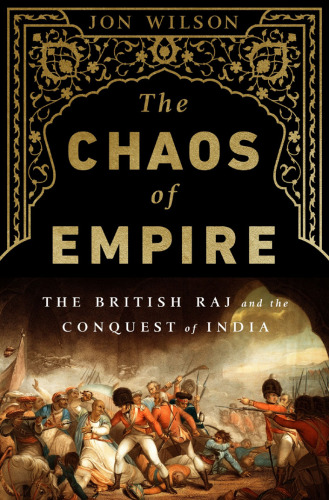

The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India de Wilson, Jon

de Wilson, Jon - Género: English

Sinopsis

The popular image of the British Raj—an era of efficient but officious governors, sycophantic local functionaries, doting amahs, blisteringly hot days and torrid nights—chronicled by Forster and Kipling is a glamorous, nostalgic, but entirely fictitious. In this dramatic revisionist history, Jon Wilson upends the carefully sanitized image of unity, order, and success to reveal an empire rooted far more in violence than in virtue, far more in chaos than in control.

Through the lives of administrators, soldiers, and subjects—both British and Indian—The Chaos of Empire traces Britain's imperial rule from the East India Company's first transactions in the 1600s to Indian Independence in 1947. The Raj was the most public demonstration of a state's ability to project power far from home, and its perceived success was used to justify interventions around the world in the years that followed. But the Raj's institutions—from law courts to railway...

Reseñas Varias sobre este libro

From Robert Clive to Louis Mountbatten, the Britons who governed in India were desperate to convince themselves and the public that they ruled a regime with the power to shape the course of events. In fact, each of them scrabbled to project a sense of their authority in the face of circumstances they could not control In practice the British imperial regime in India was ruled by doubt and anxiety from beginning to end. The institutions mistaken as means of effective power were ad hoc measures to assuage British fear. Most of the time, the actions of British imperial administrators were driven by irrational passions rather than calculated plans. Force was rarely efficient. The assertion of violent power usually exceeded the demands of any particular commercial or political interest

- Jon Wilson, The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India

In The Chaos of Empire, Jon Wilson attempts to distill the roughly 350 tumultuous years that Great Britain spent in India. He starts in the 1600s, with scattered, isolated merchants arriving on the subcontinent trying to get rich, and ends with the British withdrawal in 1947, and the partition of India into two later to be three different countries.

But this is not simply a recitation of events, but an extended act of revisionism. Wilson takes issue with what he believes is the standard view of Great Britains occupation that of a smartly administered, well-functioning empire and argues instead that it was disorganized, inefficient, wasteful, and deadly. Whether or not there is still a significant segment of people who believe that Rudyard Kiplings vision of Imperial India is factual, it cannot be denied that Wilson thoroughly demolishes the premises.

The issue I had with The Chaos of Empire is not with the content, but its presentation. When I pick up a history book, I want both good history and a good book. I want to learn, but also be entertained. Im using my free time on this, after all, and I want the minutes spent hiding from my kids to achieve maximum value.

Here, the research is solid, the endnotes extensive, the bibliography vast and varied. The writing, though, is plodding, the relentless arguments become tedious, and three dramatic centuries are rendered somewhat inert.

***

The Chaos of Empire proceeds chronologically, from the beginning of the seventeenth century to the middle of the twentieth. During this span, you see the evolution of Great Britains involvement in India. The early years are dominated by the East India Company, a corporation that took on the trappings of government in order to make a profit. Later, the Company became a purely administrative body, until it was replaced by the Raj direct Crown rule in 1858.

Meant to increase Indian participation in governance, the Raj proved a slow-motion failure, despite the protestations of its supporters. British administrators were aloof, superior, and isolated from the Indian people. Rife with racial condescension and self-interest, the Raj helped breed a national independence movement.

***

This is not a narrative history, meaning Wilson doesnt convey information by way of a story. Instead, he proceeds via analysis and interpretation. Wilson will introduce an event, and then deconstruct it to make his point.

There is nothing wrong with this approach, but there are a couple practical effects.

For one, if youre not already familiar with this subject, youre apt to be confused. Wilson doesnt really spend time telling you what happened. Rather, he assumes you already know this, and then proceeds to comment on it, usually to insinuate that prior views are wrong.

Another consequence is that an epic tale is often reduced to pedantry. There are fantastic, world-historical figures in these pages Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammed Ali Jinnah but they are not given life. There is a catalogue of high-stakes encounters, including battles, massacres, and marches to the sea, but they arrive on the page as academic facts, not life-or-death collisions.

***

To be fair, there are sections in The Chaos of Empire where Wilson seems to remember that the past was once the present, and that it involved real people in breathless moments of danger and opportunity. For me, the best parts of the book were when Wilson latched onto a character, and used that persons experiences to actually illustrate his point, rather than simply stating it.

For example, in the chapter on the law in India, Wilson follows the travails of Sayyid Mahmood, a north Indian man whod trained as a lawyer in England, rose to a judgeship on the High Court, and then was driven from his lifetime appointment by his fellow judges, who refused to treat him with equality or respect. This sequence is both vivid and memorable, while also serving Wilsons end-goals. The Chaos of Empire could have used more of these demonstrative arcs.

***

History doesnt need to be written in narrative fashion. There are a lot of methods for understanding days gone by. I want to underscore this, because my biggest issue with The Chaos of Empire is not the technique that Wilson deploys, but the execution.

In other words, I just did not his writing style.

Wilson utilizes a lot of professor-speak, reusing the same phrases, employing the occasional tortured construction, and favoring the abstract over the concrete. For instance, he states that British imperialists were driven by irrational passions, thereby taking an incredibly ambiguous notion and overlaying it across a broad section of unique individuals, who we are asked to assume acted in thrall to these unspecified desires.

As a result, The Chaos of Empire occasionally feels a people-less history of India, with the persons involved shorn of agency and driven by impossible forces and unconscious motivations. When Wilson describes a dithering Clive on the eve of the Battle of Plassey, he refuses to acknowledge Clives very human self-doubt. Instead, he believes that Clives paralysis tells us more about the mood of empire than the mind of one man. At another point, Wilson suggests that the British built roads, telegraphs, and railway lines, as a surrogate for their failure to create an ordered imperial society, without acknowledging that roads, telegraph lines, and railroads have an independent utility.

Sometimes, Wilson teeters on the verge of a parody of stilted academia. Following the 1721 killing of a detachment of Company soldiers, for example, he writes that the [m]ass murder and dismemberment could be seen as an attempt to reassert the status of Indians against a group of people who had walled themselves off from local society and humiliated the people among whom they lived.

All this is entirely subjective, of course, and I seem to be an outlier. For most people, this book apparently worked much better. Thus, you should take my opinion with a grain of salt, which has been boiled from the sea to avoid unfair British taxes.

***

The first twenty-plus years of the twenty-first century has belonged to China. Chinas trajectory, however, is not assured, and if they have a serious competitor, it could very well be India. That makes Indias history and more specifically, its conception of itself, given its history a worthwhile area of study.

Ultimately, then, The Chaos of Empire is valuable. Its big, without being overwhelming; it comes with the proper credentials; it is ably structured; and it does not hide what its trying to say, but tells you over and over again. Moreover, Wilsons judgments are sound, even if they often arrive in a manner better suited to a university journal than a thirty-dollar hardcover. Im glad I started it, and even gladder that Ive finished.british-empire india non-fiction ...more123 s Dmitri216 188

It's surprising this book hasn't received more so far. If you are looking for a recent take on the Raj there aren't a lot of popular choices. William Dalrymple has focused more on specific events while John Keay has covered a wider scope in less detail. This book has the added attraction of being written by an academic historian who has mined many primary as well as secondary sources.

Contrary to various critiques, this book does not candy coat history, nor does it apologize for past sins. It is primarily a look at the British in India, but it also considers the Indians during their rebellions, famines, and movements towards independence. The grand colonial themes of altruistic development are rightly judged as hollow polemics invented after the mutiny and massacres of 1857.

It is worthwhile as a political history. The analysis may be debated but doesn't overwhelm the narrative. Jon Wilson's thesis is a lack of strategy or ideology in the exploitation and eventual conquest beyond that of traders in pursuit of profit. This may be seen by some as akin to the Victorian historian John Robert Seeley maintaining the empire was acquired "in a fit of absence of mind."

For Wilson however infrastructure and institutions were made to transport treasure and mobilize men. Merchants became taxmen who reinvested revenues in search of further returns. Violence and coercion served to check revolts as resources were redirected abroad. Ultimately it was little more than an illusion of British power prolonged by a small number of bureaucrats and military men.

The story begins in Mughal India with early Portuguese and Dutch trading posts and the arrival of the British merchants in the Bay of Bengal. Armed conquest established rule by the East India Company from 1757 until the Indian rebellion of 1857 and the fall of the Mughals. The subsequent takeover by the Crown, called the British Raj, lasted until 1947 when nationalist movements caused it's collapse.

This is a well written book about a fascinating time and place. Covering 300 years of history in 500 pages of text and maintaining a level of focus is no easy feat. The roster of civil servants and seekers of fortune who populated the period is extensive and exhaustively compiled. At times? this history can be challenging to absorb, but it is worth the effort for those who are interested.britain colonialism india17 s David Eppenstein719 171

British history is a favorite of mine and in the course of my reading of British history I have frequently come across mentions of the East India Company (EIC) and its value to the British government. This company has become a curiosity for me since I could not understand how a private commercial trading company could become a military power able to conquer an entire country. In order to satisfy my curiosity I did try to find a book that would cure my ignorance of Indian history and give me some insight into the British Raj. I read one book last year that helped but it wasn't really a history so much as a discourse on what, if any, value the Raj was to India. I then found this book which truly is a history though for me personally a less than satisfactory history. I give it three stars because it does live up to its purpose and is worth its price but it does have its faults which may be my problem more than that of the book or the history.

I guess when I decided to discover how a business enterprise becomes a military power and conquers a nation as large and diverse as India I was expecting something other than what this book reveals. Let's say that if you are expecting this book to detail and military invasion and conquest in the nature of Napoleon or Hitler marching across Europe you will be greatly disappointed. The EIC's takeover of India was more a corporate takeover than a military conquest and was just about as exciting or entertaining. While there were certainly military events these were sporadic and relatively localized and isolated or more in the nature of large scale police actions than military campaigns. But how did the EIC become a military power to begin with was my question and this history does seem to answer it. The Answer is that it really wasn't a military power but simply hired an army for private commercial use.

When the EIC enters India it is ruled by the Mughal Empire. The emperor was a revered figure but benign in his administration of such a large and complex territory. The administration of Mughal India was left to an assortment of local nobility, kings, and warlords all of whom derived the legitimacy of their rule from the emperor in exchange for monetary tribute. The problems arose when these local authorities tried to tax the EIC. The EIC being British and arrogant beyond reason refused to be taxed by these local "inferiors" either because of racism or because they felt they had some sort of imperial dispensation from local taxing. What was really irking the EIC is that all of these local authorities had their hands out for a piece of the action and this was financial chaos for these English business types. The refusal to pay the taxes resulted in the EIC being attacked and run out of town. This humiliation at the hands of such people was more than these Englishmen could endure so they turned to the British government for help. The EIC was then allowed to basically hire elements of the British Army to act as security for the EIC in India. Because this military force was being subsidized by the company it was also under the direction of the company. The company was then able to use this military force in aggressive actions that benefited the profit motives of the EIC. The more successful and profitable these actions became the more military assistance the company was able to hire and use.

This commercial/military activity went on for some time when a rebellion threatened the reign of the emperor. The emperor asked the EIC for assistance and it was readily granted. The British put down the rebellion and in gratitude the emperor named the EIC as Collector of the Empire. This was an official government position in the Mughal Empire and was akin to being the chief administrative office of the empire. The fox was now in the hen house. The EIC set about imposing the British way of business and administration on the Indian people without consulting the people being affected. This was apparently a practice that the British would employ throughout the Raj's history. In fact, the British went to great lengths to avoid contact with the Indian people let alone discussing anything of substance with them. Needless to say the methods of the EIC were not popular and another rebellion arose. By this time, however, the emperor had become disenchanted with the British and came out openly in favor of the rebels. The rebellion was put down and because of his disloyalty the emperor was deposed and exiled to Burma. Further, to insure there would be no threat of a future reemergence of the empire the emperor's sons were all killed. The British were now entirely in control of India.

During the course of its history the EIC did experience financial difficulties that did require government assistance. The EIC had become too big to fail and many of the members of Parliament were serious investors in the company. About the time the end of the first quarter of the 19th century the British government did bailout the EIC and then insisted on government oversight of the management of the company. With that the company became a quasi-governmental operation. Shortly after the great rebellion of 1857/58 when the Mughal Empire was abolished the EIC was also abolished and the British government became the rulers of India. After this military operations became more police actions putting down rebellions or demonstrations across the country. The history then becomes one of an authoritarian, despotic, and parasitic administration bleeding India of its resources, culture, and self respect until nationalist movements begin to emerge. A period of conflict results between the forces of British imperialism and Indian nationalism until the British up and quit India with very little notice. The challenge of nation building then begins for the Indian people as well as trying to clean up the mess the British left them with when they fled India it was on fire.

But why was I disappointed in this book? First, it is just over 500 pages of text which in an of itself is not a problem if the book is well written. For quite some time I felt that the book was poorly written in that there were sentences that I had to read several times to be sure I was understanding the author's intent. A few commas would have helped. This difficulty made the book tedious to read but it did improve. I then came to wonder if it really wasn't the writing so much as the history itself. I have read about British colonial activities in other books and knew that they were utterly despicable in their treatment of colonial subjects so what they were doing in India was no surprise. While Indian independence did include significant bloodshed a great deal of it was in the nature of civil war between the Muslims and the Hindus and the British seemed to have escaped culpability and consequence for this tragedy. The creation of India was the result of politics, economics, negotiation, and persistence and I can't say that that necessarily makes for an interesting read. The book is thoroughly researched and detailed though the author does seem to be an academic that suffers from the fault of a writing style aimed for the approval of other academics rather than an ordinary reader. The book simply wasn't to my liking but that doesn't mean it isn't a good book that treated its subject in a thoughtful manner.

british-history history14 s Tariq MahmoodAuthor 2 books1,045

Probably the most balanced and subjective view on British Raj I have come across to date, an account only a British historian could deliver. That the British came to India to trade but evolved into conquerors is well known but I never knew the that the Indians always considered themselves as at least their junior partners in this colossal conquest. The Indians by this virtue demanded more rights and powers from the small elitest class of British rulers which became a sort of cat and mouse game played over a few centuries. Hindus and Muslims were both minorities who were left to fight over crumbs of opportunity left by the ruling elite class which operated as a royal class pretty much in the similar fashion to their predecessor Moghuls. The prolonged exposure to deprivation entered the Indian psyche permanently as a neurosis which exploded into full fledged civil war during the great partition of Bengal and Punjab. A Partition (of both Bengal and Punjab) demanded by the Indian National Congress as a necessary condition before they agreed to the formation of Pakistan. I now understand the shame felt by modern British every time the subject of colonisation is mentioned. This book is absolute must reading for every Indian and Pakistani if they want to get a realistic view of the history of the narrow-minded British Raj in India.british history india9 s Mary Ann424 49

I am a long-time and avid student of both British and Indian history, and I actually enjoyed this book. Although I initially found Mr. Wilson's writing style overly academic and rather pedantic (which it is), once I settled into the rhythm of it, I wasn't so bothered by it. David Eppenstein has written an excellent, detailed review with which I heartily agree, so I will not repeat his thoughtful and comprehensive critique. Although I was familiar with the basic facts, I found the first part of the book particularly informative in its detailed account of the 17th century beginnings and 18th century growth in power of the East India Company which was virtually unquestioned and unchecked by the British Parliament with utterly no cognizance of or concern for the economic, political, legal, social, and cultural norms of a diverse native population. Not until the early 19th century (and from here on I was in familiar territory), as Britain's paramountcy was threatened by competition and the Company's reduced profits (always the overriding concern), were voices raised, however ineffectually, to examine more critically the enterprise and its practices. I also thought the author's account of the causes and circumstances around the great rebellion of 1857 to be well done. Whatever consideration for the welfare of the peoples of the subcontinent that might have developed vanished as the British government dug in its heels and took direct control from the EIC with a tortuous and self-serving effort at moral justification that its policies served the long term interests of the natives whose natural "inferiority" was deemed to render them incapable of any form of self-determination however limited. The late 19th century rise of political opposition by increasingly well-educated Indians (many English-educated and trained) and the eventual establishment of the Indian National Congress in the wake of widespread famines, British work camps, and outbreaks of disease is narrated well, as is the disastrous 1905 partition of Bengal, under the Viceroyship of Curzon, which set the stage for religious separatism. Poor India. Just when it appeared that slow progress might be occurring in the second decade of the 20th century, the Great War intervened, and all bets were off. The period between the world wars, Britain's very sudden abrogation of responsibility resulting in India's independence and partition after centuries of relentless suppression is covered rather hurriedly and less comprehensively. It's a tragic story, but given its vast scope, I thought Mr. Wilson, on the whole, did an excellent job.history-politics-government non-fiction7 s Sajith Kumar625 111

Now that there are numerous books on the British occupation of India that witnessed two centuries of colonial rule, any new author on the subject is burdened with having to provide a guarantee to the reader of providing at least one previously unknown fact or story in the book. On this aspect, this book is a treasure chest of new knowledge on the colonial rule. Most Indian books on the subject sing the eulogy of Jawaharlal Nehru and his Congress party in snatching freedom away from the British. They typically follow a political narrative of the era. Wilson follows a refreshingly novel approach that of the economic and social analyses. Gandhi and Nehru appear in several pages, but not more than that, which is the most deserving representation that is warranted by circumstances. This book describes the economic factors that shaped politics and the feeling of insecurity which was firmly rooted in the minds of British administrators. Wilson argues that they had no further agenda than displaying British power and obtain submission of Indian people before the Empires might. The British also introduced constitutional reforms that changed the way Indians governed themselves. These were slow at first, initially coming at a time when the Catholics didn't even have the vote in Britain. This book presents a continuous story of how the British conquered India and how it was forced to forego the jewel in its crown, spanning four centuries. Jon Wilson is a professor of history at King's College, London having educated at Oxford and New York. He is an expert in Indian history and has authored another book on the subject.

The English East India Company was a merchant establishment who assisted the crown in establishing a lucrative colony in India. Most historians would stop at this description but this author informs us how it was much more than a mere trading company. From the start, the company was a political body with a single stock of money to hire ships, pay soldiers and build warehouses (called factories). It was empowered to sign its own treaties with local rulers. The crown gave it monopoly on trade with all parts of Asia not in the possession of a Christian prince. At least on this point, they were not much different from the Portuguese who came to India in search of Christians and spices. When it acted, it did so with the command of the English state. The company tried to squeeze themselves into the already crowded Indian trade, with a bid to claim tax-free status. This was resented by Mughal governors. The first attempts to challenge the Mughal state ended in catastrophic disasters in 1689 in Bombay and Bengal.

Aurangzebs death marked the beginning of the end of the Mughal dynasty. Wilson identifies the invasion of Nadir Shah that catalysed the downfall. Nadir Shah's symbolic sovereignty over Delhi lasted only 57 days in 1739, but its aftershocks transformed Indian politics. It massively shrank the sources of Mughal power, leading to lawlessness in the provinces. Mounted warriors ransacked the countryside seeking wealth. Plunder and not negotiation became the effective tool for creating centres of wealth. Credit networks temporally disappeared, making it harder to send money. Trade collapsed and it took public finances along with it. This turned out to be a most opportune moment for the East India Company. Victories against Arcot and Mysore in the peninsula and against Siraj ud-Daula at Plassey had transformed the British from armed merchants to tax collectors. This came about by a clever change in company policy. In return for lending soldiers and money to Indian rulers, the company was entrusted with land from which the money owed to them could be recovered from the taxes accruable. Nizam of Hyderabad had to cede 30,000 square miles of territory in Andhra which was later known as the Ceded Districts.

For better or for worse, the company introduced many novel reforms that disrupted the political fabric at first, but continue to remain with us to the present day. The practice of decision making in writing inaugurated an era of hefty paperwork, but it moved decision-making away from public view in contrast to the open display of authority under the Mughals. Another crucial factor enhanced the military potential of the company. Its victories in battle were not the results of technological or tactical superiority. They were simply better at raising enough money for the campaigns through deficit financing. The company's unrivalled ability to borrow cash from global money markets ensured a reliable source in times of dire need. This was augmented with revenue collection and part of bullion borrowed from London for trade with China, but used for military purposes. It also borrowed from Indian merchants and bankers at 5 to 7 per cent of interest. Compared to this, when the Marathas ran out of cash, their soldiers ravaged the countryside to extract payment from the villagers which caused much acrimony and resentment.

British conquest of India was confirmed with the defeat of the 1857 Mutiny. Wilson follows an attitude sympathetic to Indian interests. The most brutal massacres executed by both sides were at Kanpur where 200 white women and children were killed by the mutineers and many times that many Indians were killed by the British in retaliation. Wilson ameliorates the sepoys by claiming that the killing probably took place because the sepoys had become increasingly frightened about being attacked themselves(p.243). Justifications of this kind are way off the top. Similarly, the last Mughal emperors picture also gets a sympathetic brush. Wilson claims that Bahadur Shah Zafar shaped the rebel government making sure sepoy leaders were not displaced by nobles, provided moral sanction for the new regime and then tried to use his authority to direct it away from excessive violence. This is in contrast to the image drawn by other historians. Just compare it to William Dalrymple's The Last Mughal where instances when the sepoys were disrespectful even to the physical presence of the emperor are narrated. This book examines the finer nuances of the concept of Rule of Law implemented by the British regime. The penal codes priority was the smooth and safe functioning of the imperial administration. Punishment for crimes against individuals was only a sidekick. Ten sections of the code dealt with offences against the state and nineteen covered actions contemptuous of public servants, while only three sections dealt with murder and four covered other forms of culpable homicide. The strange fact is that modern India still retains them.

Wilson rewrites the official narrative of Indian Independence struggle which is monopolized by the supposed larger-than-life antecedents of the Congress party. India's political movements were planted and nurtured by local industry leaders. Growth of the textile industry in Ahmedabad in the 1870s made a rich business class. The inferior political position of India's leaders hampered their trade. The profitability of business and prosperity of the country needed a new kind of political leadership able to put Indian interests first. Similarly, the freedom struggle is often portrayed as a 24x7 fight of Congress leaders against the inhuman British polity. This is also very far from the truth. The constitutional reforms of 1919 introduced a very limited form of self-rule, but it demoralized the imperial bureaucracy. The clash between British officers and Indian political leaders within and outside the local institutions caused the capacity of imperial administration to collapse in the early 1920s. In many towns, villages and districts, public offices flew Congress flag and ensured that government-funded schools taught anti-British curricula. Judiciary and higher education became almost fully Indianised.

The book can be condensed into a single paragraph given on p.481 which runs as follows. Rather than a coherent political vision, British rule in India was based on a peculiar form of power. Fearful and prickly from the start, the British saw themselves as virtuous but embattled conquerors whose capacity to act was continually under attack. From the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries, they found it difficult to trust anyone outside the areas they controlled. Their response to challenge was to retreat or attack rather than to negotiate. The result was an anxious, paranoid regime. The British state was desperate to control the spaces where Europeans lived. Elsewhere it insisted on formal submission to the image of British authority. But it did not create alliances with its subjects, nor build institutions that secured good living standards. The British were concerned to maintain the fiction of absolute sovereignty rather than to exercise any real power.

As earlier mentioned, the book describes many previously unheard of hard facts and provide an economic perspective to Indian history and freedom struggle. Though it examines the effect on Britain of ruling over India for two centuries and then suddenly letting it go in 1947, a similar survey of the effects of British rule on India is missing. This may probably be as a result of the authors careful intention to be on the right side of Indian readers and appear to be politically correct to them. The book includes some lacklustre photographs which don't do much justice to the subject. What is astonishing is the huge size of the bibliography, much of which can be freely downloaded from archive.org for serious readers wanting to pursue a specific topic.

The book is highly recommended.

history india-s-freedom-struggle5 s Vidur Kapur124 48

Shortlisted for the Longman-History Today Prize in 2017, The Chaos of Empire is a gem of a book, fully deserving of the praise it has received from historians, economists and journalists. I was alerted to its existence when reading the blog of a prominent American economist, but it seems that outside the world of academia and journalism, few have heard of it, in contrast to works by William Dalrymple among others. The major complaints about the book seem to concern the author's academic style of writing, but for my part I thought that the writing was engaging.

Dr Wilson is a historian at King's College London and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. This book, the product of years of meticulous and painstaking research drawing on primary and secondary literature, presents the thesis that the British Empire in India had no real purpose except to maintain its grip on territory through force and violence. Contrary to the asseverations of both apologists for and critics of the despotic regime, the British did not have a mission to transform India. As Wilson writes:

This book has challenged these myths of imperial purpose and power propagated on both the political left and the right. Looking at empire from the bottom-up, through the real lives of its functionaries and subjects, we see how imperial power was rarely exercised to put grand purposes into practice. Its operation was driven instead by narrow interests and visceral passions, most importantly the desire to maintain British sovereign institutions in India for its own sake... It left no purpose, culture or ideology.

From the 1680s to the 1850s, the East India Company attempted to conquer parts of India for one purpose only: to raise revenue. Indian regimes did sometimes invite the British to settle in their territory in order to act as a bulwark against competitors; Robert Clive, who would later establish the Company's control over Bengal, first made his name as part of a Company force acting as mercenaries for the Mughals. But though the Company did maintain relationships with Indian rulers within the Mughal and Maratha systems, they were often fractious. It was a world of shifting loyalties and alliances, in which competing Indian regimes, as well as the British and for a time the French, were jostling for power.

After a string of defeats at the hands of Mughal and Maratha forces for 70 years, Robert Clive established British sovereignty over Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The Company finally got the special status it had craved, and assumed revenue-raising powers. Now that it had real power, it was not about to show any kind of flexibility. Wilson excoriates the Company's actions in Bengal in the subsequent decades, arguing that the breakdown of the consensual political system in place under the Mughals, combined with the impatient focus on the collection of revenue at all costs, was a major cause of the Bengal famine of 1769-70.

Wilson estimates that 3-4 million died in this famine; others put the figure as high as 10 million. As Wilson notes, such a devastating famine hadn't occurred in Bengal since 1574, when the Mughal conquest of Bengal had only just began; even the bad harvests of 1737 and 1738 did not create large mortality rates. Even after the famine had occurred, the East India Company offered no relief. It "evaded the responsibility that Indians (or, for that matter, the British in Britain) thought were a consequence of sovereign power", Wilson writes, in line with his overarching thesis.

The East India Company attracted considerable criticism from within Britain over the next few decades as it continued to acquire territory. Criticism was primarily directed at the corruption of Company officials, but concerns about the welfare of Indians were sometimes raised. Reforms were therefore periodically proposed. At times, they weren't enacted, and those reforms that were enacted were counterproductive. The reason for this, Wilson posits, is that 'reform' was only ever an attempt to regain control of events, so as not to lose power.

For example, toward the end of the eighteenth century, the liberal conservative philosopher Edmund Burke and the Governor-General of India Warren Hastings both believed that India had been better ruled before the British conquest, but differed as to how the situation should be remedied. Wilson's exposition of their views is fascinating. Suffice it to say, Burke won the argument, leading to a new system that was implemented in the 1790s in Eastern India, predominantly in rural areas. Yet:

The system undermined the negotiation and face-to-face conversation which had been so essential to the politics of eighteenth-century India. As a result, it brought dispossession and the collapse of a once rich region's wealth... The new system was not designed to create a stable political order in the Indian countryside. Its aim was to defend the integrity of the East India Company from accusations in Britain of venality and vice... the colonial regime's new insistence on the rigidity of its revenue demand had a bad, sometimes catastrophic impact on local livelihoods. Lords did not have the money to invest in the infrastructure needed to maintain local prosperity. As a result irrigation canals silted up, roads fell into disrepair, ferry men went out of business and markets declined. Production shrank in western Bengal and Bihar.

In the north, west and south of India, meanwhile, the East India Company conquered territory between 1800 and 1850, as a result of its "unrivaled ability to borrow money from global money markets" to fund warfare. Indeed, "British expansion was funded by debt". But the expansion also led to what Wilson calls a "chaotic conglomeration of different establishments"; there were at least four different kinds of regime in India by 1830.

This leads Wilson on to provide a fascinating account of the attempt to exploit utilitarian principles to centralize power in India. Though 18th and early 19th Century liberal intellectuals such as Adam Smith, Burke and Bentham were all critics of imperialism (the latter objecting to it on utilitarian grounds), by the 1830s their successors worked in concert with Tory imperialists such as Elphinestone, Metcalfe and Malcolm to formulate a system which, if implemented at home, "would have alarmed the most autocratic Tory in Britain". As per usual, "it was justified on the basis that British rule was under threat in India in a way it wasn't in the British Isles"; while liberals and Whigs opposed the authoritarianism of Tsarist Russia and Metternichian Austria at home, they thought that Britain should emulate Russian practices in India.

With centralization came a number of projects which later imperial apologists would use to attempt to defend the British presence in India. But even these projects were not part of an attempt to transform India. Wilson compellingly demolishes the mythology surrounding the construction of the railways and the (slow and halting) development of legal reform. The construction of the railways was carried out "to protect the Company's power in India from challenge", not to improve lives; the "advantages that public works bestowed on Indian society were very limited... Neither railways nor irrigation systems had much of an impact on the livelihood of most Indian workers... Most importantly, they did not prevent famine".

Railways, in other words, were just another way to project the Company's power and sovereignty, and weren't emblematic of a wider attempt to remake India in Britain's image, or to proselytize Christianity, which some observers of the Indian rebellion of 1857-8 suggested was the cause of the discontent. As Wilson contends:

there is little evidence that the East India Company attempted to transform Indian society... nor is there any evidence that Indians rose up against efforts at reform... It was an insurgency against an anxious regime's counter-productive effort to hold on to power... driven by the East India Company's fearful effort to destroy any centres of authority in India that displayed the smallest flicker of independence.

Indeed, the legal reforms that were proposed back in the 1830s weren't enacted until the 1860s and 1870s. Though they were heavily biased against Indians, their purpose was, again, to allow the British to hold onto power, not to moralise. Although the reforms of the 1830s had conceded that Indians should be able to take official positions in society, the reality was that any attempt by Indians to gain a foothold in the legal profession and the judiciary was fiercely resisted.

It was against this backdrop of defeat in the rebellion and continued exclusion from positions of power that Indians started to promote self-reliance. Self-reliance was distinct from self-rule: in this period of Indian resistance to British rule, Indians began to rely on their own parallel institutions and organisations, especially after famines in the 1870s and 1890s - killing millions - further emphasised the apathy of the British.

It was in the economic sphere that Indian efforts would have a lasting impact. Many Indians were incensed by the prevalence of poverty in India. Some attribute this to a drain of wealth from India to Britain, but this is not entirely accurate, Wilson argues. While it is true that Indian producers were starved of resources, this is because the agency houses and the imperial bureaucracy "blocked Indian access to global capital markets" and "insisted on maintaining rigid racial barriers". There was a ban on Indian-made steel in place until 1899, with restrictions on the mining of coal and iron ore also in place.

Thus, Indians began to rely on their own sources of capital and their own financial institutions, creating a number of banks that continue to operate to this day. Indian entrepreneurs subsequently relied on these networks. As Wilson writes:

Economic growth and institutional dynamism occurred in the places that were furthest from the rule of British bureaucrats... [For example], Tata created a series of settlements and institutions beyond the reach of imperial power... Tata located India's first modern steel plant in the Chota Nagpur plateau in eastern India, building the new town of Jamshedpur between 1908 and 1912. From the beginning, the town was administered by an Indian company not the government.

At times, self-reliance coincided with self-rule. India's 'native states', which constituted 45% of the total area of India and included around 23% of India's population, were ruled by Indian princes with minimal British involvement, except in matters of defence. Wilson writes that these areas:

pioneered research in science, technology and the growth of banking. It was the Maharaja of Mysore, Sir Krishnaraja Wodeyar, not one of the Raj's British provincial governors, whom Jamestji Tata persuaded to open India's first Indian Institute of Science in 1909. India's first large-scale electricity-generating plant was built in Mysore, too. The state of Baroda launched one of India's most successful nationalist banks.

This corroborates recent papers by economic historians which suggest that areas of India ruled directly by the British "did not invest as much as native states in physical and human capital." For example, the native state of Travancore announced a policy of free primary education as early as 1817; compulsory primary education was first introduced in the native state of Baroda in 1892, while the British passed a compulsory education act in the nearby Central Provinces only in 1920, due to pressure from Indian politicians. Overall, estimates suggest that the native states invested twice as much in education than the areas under direct British rule.

However, the highly controversial partition of Bengal in 1905 - reversed in 1911 - emphasized to many Indians that self-reliance, which was bearing fruit, was not going to be enough. Self-rule was needed throughout India.

Once again, imperial bureaucrats were anxious to act quickly to preserve the empire. They only differed on how to achieve this: the Tories thought that any concessions would lead to the downfall of the empire, but the Liberals took power in 1906. Viceroy Harding wrote in 1911 that demands for more democracy would have to be satisfied.

"Liberal imperialism", however, was always going to collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. As Wilson points out, the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, which introduced a degree of democracy into India's political system, "still retained some of the authoritarian and despotic attributes of the previous system". The Amritsar Massacre of 1919 was triggered by laws which allowed for detention without trial and arrest without warrant. It was condoned by much of the imperial bureaucracy, emphasising that the imperial regime still intended to suppress dissent by force.

Despite the contradictions of liberal imperialism, Indian politicians did take advantage of the semblance of democracy, rapidly improving medical infrastructure, introducing compulsory primary education, and constructing hydro-electric schemes. Nevertheless, the demand for further democracy could not be held off for long, and elected politicians were given full control of provincial governments in the mid-1930s, with a power-sharing executive. This was just another "compromised effort to stave off crisis", Wilson argues: the purpose of the reforms was to fragment India and prevent the establishment of a central, national, democratic government.

British treatment of Indian soldiers during WWII would only intensify calls for self-government, which Churchills government begrudgingly promised would be implemented after the war (as a self-governing 'dominion' Canada). Indian society was mobilized for one final push against the Japanese. But after the war, the fragility of the British presence in India was obvious. It was impossible for the British to again use force to counter Indian resistance.

After independence, with the British out of the way, the self-reliance and institution-building that Wilson expertly illustrates earlier on in the book was finally able to take hold across the whole of India:

newly independent India... invested in science and technical education, built heavy industrial plants, founded new colleges... Compared to the stagnant chaos of British rule, living standards improved... [the economy] increased by 4%... only very slightly slower than the contemporary 'miracle' of France.

Wrapping up his thesis, Wilson points to the abrupt departure of the British as evidence that British power was only maintained for its own sake. The empire "left no purpose, culture or ideology". It came, and it went.history indian-history4 s Edoardo AlbertAuthor 51 books142

Question: how long does a guilt trip last? Answer: 504 pages. Let this reviewer nail his colours to the mast: he is a child of empire. His fathers family worked for, kowtowed to and adopted its name from the British. We were condescended to and condescended in our turn. And we ended up here. But, the rest of the subcontinental diaspora, and the people of India and its surrounding nations, weve gotten over it. Ploughing through Wilsons work, it would appear the author hasnt. Not that Wilson doesnt know his Marathas from his Mughals: theres much of interest in this long telling of Britains involvement in India. What lets it down is the refracting lens through which Wilson views everything. The British are invariably portrayed as rapacious, violent and fearful, trembling in cantonments for fear of the brown-skinned hordes without. But those occasions when Indias native rulers, killed people in their thousands are either passed over or excused. One begins to suspect that the author may have transposed a morbid revulsion at UKIP voters into his reading of the past. So his portrayal of 18th-century Englishmen bears close comparison to todays media reports of the people who voted for Brexit. At the same time, every possible mitigating circumstance is accepted for the violent actions of anyone with brown skin. For instance, when a group of 120 men of the East India Company are mutilated and killed in the most brutal fashion, we learn that this was an attempt to reassert the status of Indians against a group of people who had walled themselves off from local society. Now, Im not that keen on gated communities myself but Im not sure that makes it all right to chop someone into pieces.

Wilson is concerned to destroy the idea of the Raj as a planned and organised imperial enterprise but, seriously, who actually holds such a view? The Raj was, from the beginning, a bootstraps and banana leaf enterprise, responding to circumstances rather than following a plan. Yes, Wilson succeeds in his enterprise, but the opponent he is tilting at is mostly filled with straw.

The myopia continues throughout the book: British bad, Indians good. In the end this is a book not so much about the chaos of empire as the guilt of empire.4 s Edoardo AlbertAuthor 51 books142

Question: how long does a guilt trip last? Answer: 504 pages. Let this reviewer nail his colours to the mast: he is a child of empire. His fathers family worked for, kowtowed to and adopted its name from the British. We were condescended to and condescended in our turn. And we ended up here. But, the rest of the subcontinental diaspora, and the people of India and its surrounding nations, weve gotten over it. Ploughing through Wilsons work, it would appear the author hasnt. Not that Wilson doesnt know his Marathas from his Mughals: theres much of interest in this long telling of Britains involvement in India. What lets it down is the refracting lens through which Wilson views everything. The British are invariably portrayed as rapacious, violent and fearful, trembling in cantonments for fear of the brown-skinned hordes without. But those occasions when Indias native rulers, killed people in their thousands are either passed over or excused. One begins to suspect that the author may have transposed a morbid revulsion at UKIP voters into his reading of the past. So his portrayal of 18th-century Englishmen bears close comparison to todays media reports of the people who voted for Brexit. At the same time, every possible mitigating circumstance is accepted for the violent actions of anyone with brown skin. For instance, when a group of 120 men of the East India Company are mutilated and killed in the most brutal fashion, we learn that this was an attempt to reassert the status of Indians against a group of people who had walled themselves off from local society. Now, Im not that keen on gated communities myself but Im not sure that makes it all right to chop someone into pieces.

Wilson is concerned to destroy the idea of the Raj as a planned and organised imperial enterprise but, seriously, who actually holds such a view? The Raj was, from the beginning, a bootstraps and banana leaf enterprise, responding to circumstances rather than following a plan. Yes, Wilson succeeds in his enterprise, but the opponent he is tilting at is mostly filled with straw.

The myopia continues throughout the book: British bad, Indians good. In the end this is a book not so much about the chaos of empire as the guilt of empire.4 s Bhuvan Chaturvedi2

I finished ploughing through this 500 page book yesterday. The primary hypothesis the author seeks to prove is that the British rule was sustained by violence and authority as opposed to the earlier Mughal period characterized by negotiations and intricate support networks within rural and urban society. This is supposed to counter the romanticists version of the British time as a period of order. However, this is a fringe and ill-founded view, at least among Indians. The author has devoted many needless pages to prove why pursuit of prestige and dominance was the sole justification the British had in their own eyes for their India empire. This is a given, and is by and large true for all imperialistic enterprises and not much is gained by seeking to prove this. However, often times military conquest by foreign powers does introduce changes in society which would not be possible otherwise, or come too slowly. So while the British introduced many changes to improve the exercise of their authority, those changes had unintended positive spin-offs. The author has completely ignored this aspect.

The second issue I take with the book is the glittering account of Mughal times, even including a whitewash/explaining away of Aurangzeb's excesses. Towards the end of the book, this treatment is extended to Jinnah's communal politics by positing an equivalence between the communal demands of the League and the inclusive agenda of the Congress. However, when I see references to the JNU and Aligarh 'eminent historians' in the book, it is to be expected that there will be a complete glossing over of religious motives for Muslim kings and politicians.

In the final analysis, if you limit yourself to proving a point, you will find enough corroborative evidence and can always leave out whatever does not fit your theory. This is a lawyer's method that is adopted by so many historians now. Can these historians lift their gaze over the sweep of history and paint an integral picture?4 s John940 120

This was the last book that I purchased whilst browsing around in a bookstore (Crow Bookshop in Burlington, Vermont) just before the crisis. In that odd first week of March, where everything was completely normal, until all of a sudden it wasn't. I think of that every time I look at this book. If I had known it would be many months before I could browse a bookstore again, I would have purchased more books.

I bought this because I was lecturing on the East India Company and the Mughals, and I figured that I could get some good material out of this tome. And I did! My class last semester was World History up to 1800, so I read the first couple hundred pages and used some of that material, and then I didn't pick this up again for a while. Now I am prepping for WH 1800-present, so I am dog-earing the pages again. The trouble is, this book is a little bit too long. I was hoping that not only would I get lecture material, but that I would also understand the history of the Raj a little better, and I don't feel that really worked. I had to start skimming around page 350. Wilson does have an argument here, about how the British never really had a lot of control and power in India, but tended to overreact and ASSERT power all the time, as kind of a coping mechanism for feeling insecure. That is a good lesson for a world history class. And there are some great anecdotes and quotes that help explain Indian attitudes toward British rule at various times. But I couldn't assign this in any way, it is just too much. Too much happening. Maybe a book about how British rule was kind of chaotic is fated to be kind of a chaotic read? Definitely worth keeping on the shelf though. 2 s Rohini Kapur11

I had bought this book for my spouse, who is a big history buff. I ended up reading it. History was the most boring subject for me in school, and I set this book as a challenge. And I absolutely enjoyed the challenge.

The author Jon Wilson begins with an explanation of the early British interest in India up to independence and its aftermath. Right from the beginning, the author says, they created problems wherever they went. They refused to deal with local leadership in Indian / Mughal style (negotiation, understanding and give-and-take), instead they wanted to impose their own ways. If their demands were not met, they responded with aggression.

Written in chronological order, the book begins even before the Battle of Plassey and goes through important events of the British Raj, from the Maratha wars to the famines, and how the British dealt with all these situations.

Since India Conquered is written by an academic, it took me time to get used to the style and I had to pause several times to evaluate what I had just read. So halfway through the book I began taking notes on post-its and sticking them into the book. That helped a lot and soon I was deeply engaged. The book opened up several new ways of thinking about the British Raj. Primarily, it debunked myths about what the British really did in India. They had no plan, no strategy, they responded with violence to anything and everything, and in the end, it was all about British pride. They ruled India with chaos and they left India in chaos.

It took me a very long time to read this book (it is a difficult read for those not used to academic, text-book styles), and despite the form and style, I loved it. And I would recommend to anyone who wants a new perspective on British Raj.

history india nonfiction2 s Drasko Kovrlija52

Great overview of the British rule of India, but the author's strong bias is a significant distraction1 Pj Mensel140 3

This is a great book for those interested in piercing through the BS British historians have been putting out about the British Raj. A detailed look under the smokescreen (using many Victorian and native Indian sources) that the British establishment had put out for centuries on how Britain attempted to civilize India (in the process attempting to make irrelevant a culture that had endured for centuries. The British are lucky Gandhi was around, otherwise they probably would have been murdered in their beds many times. They NEVER had control of India - they just attempted to control it by force and terror. 1 Tom NixonAuthor 20 books10

A solid and well-researched history of British rule in India, Jon Wilson's India Conquered aims to provide a reassessment of a lot of the mythology of the British Raj and I think he more or less succeeds in his goals. The general notion that Wilson is exploring with this book is the idea that British rule in India was coherent and powerful- while the reality is that British rule was uneven and based on violence and the use of force- and left behind a piecemeal patchwork of economic development in their wake.

I think you can challenge Wilson's argument on some points- some notes on the wiki-page for the book point out that his analysis of the period prior to the British is somewhat lacking and that there's a lot of hand-wavey generalizations that pop up over the course of the book. Nuance, naturally, would undermine a lot of Wilson's thesis- or at least if it didn't undermine it, it would certainly distract from it.

The point about the generalizations is true enough, but the real interesting critique I think is about his lack of analysis of the latter stages of Mughal rule. Granted I haven't done academic-level deep dive readings on late-stage Mughal rule, but there are similarities between the structure of Mughal rule versus what the British eventually end up setting up in the Raj. My gut instinct really depends on how the Mughals were viewed by the time you get to the period just before the British arrived. If they were still seen as outsiders partnering with local elites to provide a sort of overlordship then pre-1857 that seems to be the model the British were trying to emulate- and you can argue that with the number of princely states that were left technically independent after 1947, elements of this model sort of remained throughout.

But Wilson's argument becomes a lot more solid with post-1857 British rule in India. After the Mutiny, the British were undoubtedly nervous, more cloistered together, more distrustful of Indians and more inclined to use force to back up their rule. His notion that the infrastructure and economic development the British began to embark on only benefited Indians in passing or tangentially is a convincing one.

Railways came fairly late to India and they were mainly implemented not to spur economic development or investment in India, but to make sure there was the right infrastructure to move British military forces around quickly in case they needed to be so. The struggles of Tata Steel- still a major company in India today- to get started and off the ground only underlines Wilson's argument: the British interests were their own and they weren't necessarily about developing the Indian economy-- and what's fascinating about this point is that as Indian elites began to realize the level of disinterest the British had in actually developing the Indian economy the early nationalist movement began to grow a sort of parallel economy, where you can do business at Indian-owned banks, etc, so on and so forth.

The eventual withdrawal of the British and the chaos of Partition also serve to buttress Wilson's argument. The British just left. There was no serious attempt to hold onto India or the integrate into deeply into the Commonwealth. Britain realized it couldn't hold on and that was more or less that. Any pretense that India was a vital part of the British Empire and would never be surrender more or less vanished overnight- which only serves to prove that the British were, as Wilson suggested, more interested in their own interests and if they happened to deliver some benefits, tangible or otherwise to Indians, that was a happy accident more than designed by policy.

(There's an interest alt-history notion to consider and probably abandon, but if India had been granted Home Rule and Dominion Status as a response to say, The Mutiny-- or maybe in the early 1900s, perhaps- how different would things have turned out? It's doubtful it would have ever happened, but it's intriguing to consider.)

Overall: if you're looking for a solid and unsparing history of the British Raj, this volume is pretty decent. It doesn't put on the rose colored glasses- in fact, it actively tries to avoid them and the result is pretty good and it's not a door stop either. Wilson's writing is approachable and readable-- this isn't a dry and dusty academic tome and I went through it pretty quickly. My Grade: **** out of **** Ajay252

The British have ruled territory in India from the 1650s. Even past Indepence, it is a country whose history, culture, language, and identity have been irrevocably shaped by the imperial past. It is easy to imagine this legacy to be the remains of a powerful and purposive regime. Britons and some Indians, look back on the 'Raj' as a period of authority, peace, and order - a time when 'Pax Britannica' imposed reason and order on a confusing and fragmented society and corruption or violence was less rife than today.

There is reason to hope that such things were true - modern India suffers from enclavism, where the wealthy and powerful close themselves off from those less fortunate, factionalism, as those who remain outside the enclaves form groups to argue for their own interest, and both corruption and poor governance on an unparalleled scale. Perhaps, these faults lie with a lack of leadership or the inherent complexity of the 'Indian National Project".

This book shows how those perceptions are wrong. They are rather, the projections of the British Imperial Admin

Autor del comentario:

=================================