oleebook.com

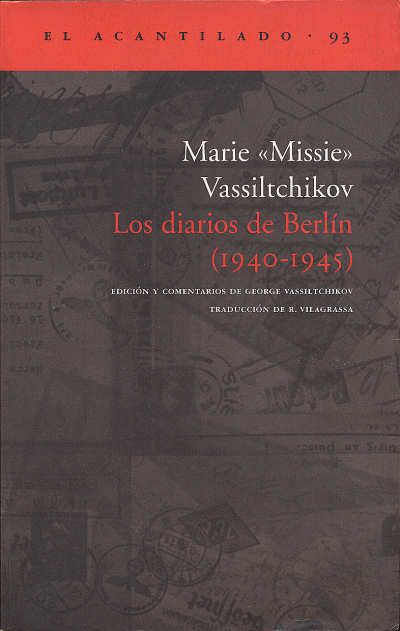

Los Diarios de BerlûÙn 1940-1945 de Vassiltchikov, Marie

de Vassiltchikov, Marie - Gûˋnero: Ficcion

Sinopsis

Marie ô¨Missieô£ Vassiltchikov abandonû° Rusia con su familia en la primavera de 1919. Sorprendida por el inicio de la Segunda Guerra Mundial cuando pasaba el verano con su hermana Tatiana en el castillo de la condesa Olga Pû¥ckler, se vio obligada a buscar empleo en BerlûÙn. En enero de 1940 comenzû° a trabajar en el Servicio de Radiodifusiû°n y mûÀs tarde en el departamento de Informaciû°n del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores del Tercer Reich, en el que colaborû° con un nû¤cleo de adversarios del nazismo que mûÀs tarde se hallarûÙan implicados en el fallido atentado del conde Von Stauffenberg contra Hitler. De esto tratan estas pûÀginas, diario personalôpublicado por vez primera en 1985ôque nos acerca al BerlûÙn del final de la guerra y sus cûÙrculos antinazis.

ReseûÝas Varias sobre este libro

Upfront: I would rate this book zero stars for its literary value but 5 stars for its highly interesting contents.

If you are interested in historical facts connected with WWII (especially the failed bomb attack on Hitler by Count Stauffenberg and his allies, who had planned to not only kill Hitler but to overthrow the Nazi regime), this book is a must-read. If you are looking for literary value, do yourself a favor and stay away from this book.

This said, I am attempting to review this book, which is not an easy task.

I need to divide this review into different parts and also evaluate this book from different aspects.

First, I would to mention that this book contains 46 photographs, most of which I found interesting.

And now it gets difficult. The author died in 1978, at age 61. ôDe mortui nil nisi bene. (Donôt say anything but good about the dead.)ô I am sorry, but if I wanted to adhere to this, I could not possibly review this book. So I must disregard this command.

The first half of this book is not really what I would call a diary; it reads more the log book of an escort, registering dinner outings with friends and acquaintances of both sexes (almost all of which aristocrats) and attendances of a seemingly endless succession of dance parties and other celebrations (at various embassies but also at private castles and mansions) with aristocrats, political higher uppers, and other celebrities. All this while WWII was raging, Berlin was being bombed, and while people were dying in collapsed or burning buildings, or just simply in the streets, hit by flying debris.

Apart from that, I have never found as much name dropping in any book I have ever read. Everybody the author had to do with seemed to be a prince, a princess, a count, a countess, or at least, a baron, a baroness, or a celebrity, such as a famous fighter plane pilot or a movie star. Not that I am allergic against name dropping. I can usually take quite a bit of it before I get annoyed, but whatôs too much, is too much! Well, maybe this wasnôt the authorôs fault. She just lived in different social circles than I did.

What really puzzled me, however, was why the author would be invited to so many dinners, parties, and other events. All right, she was an aristocrat, a Russian princess whose parents had fled with their children from the Russian Revolution to settle in Lithuania, where they had owned an estate, and from which they had to flee again, this time to Germany, when the Russians invaded the country after Hitler had invaded Poland. Nice to learn that aristocrats stick together and help each other in need. But does this mean that they have to continuously invite each other to restaurants, private dinners, dance parties, and overnight-visits?

Letôs face it: The author, while educated and multilingual, did not seem to be overly intelligent. (Otherwise, she would not only have acted but also written in a different way.) Thus, she was unly to have been a highly sought-after conversation partner.

And what puzzled me even more: How could she possibly have had the means to go out about every second night, quite often walking long distances on foot? Mind you, she was invited and didnôt have to pay for the food or drink. (Lobster and oysters, she reports, did not require ration stamps. And there always seemed to be wine and champagne at first choice restaurants and hotels, as well as in private castles and mansions.) However, shoes wear out, especially when walking on pavement. They also wear out with dancing. Stockings wear out even faster. And there was a terrible shortage of shoes and stockings during WWII. You needed coupons to buy clothes, shoes, stockings, and other non-food items. These coupons were never enough to purchase supplies for normal wear. (Besides, when there was no merchandise in the stores, coupons would not buy you anything.) How could one possibly obtain sufficient amounts of shoes and stockings for excessive wear?ôYes, there was a black market. If you had tons of money, you could probably buy anything. But the author did not have tons of money. She keeps complaining throughout the book that, with her earnings (first working at the German Broadcasting Service, then at the German Foreign Ministryôs Information Department, and later, in Vienna, as a nurse), she could barely make ends meet. I donôt get it. Something is amiss here.

What also irritated me quite a bit: Why did this woman not stay put? Why did she have to travel incessantly to meet other aristocrats at far-away castles, taking extra time off work (annoying, quite understandably, her bosses)? Why did she (with lots of luggage!) have to take up space in railway wagons overfilled with stressed refugees from firestorms of carpet-bombed Hamburg and, later, carpet-bombed Berlin? Why was she not content when her office was evacuated to a ski-resort far away from Berlin, where she was considerably more safe than in the capital? Why did she have to make up stories to get to travel back to Berlin (which was, meanwhile, also carpet-bombed)? She mentions that she was bored being away from the big city. Would you be bored being away from a city that was carpet-bombed and where people died by the thousands in almost daily air raids? I wouldnôt.

So many questions remain unanswered here.

The author never explains the exact hierarchy of the employees at either of her places of employment. I would have been particularly interested in the hierarchy at the Foreign Ministry, where a number of the Stauffenberg plotters had worked. Adam von Trott zu Solz did not seem to be the authorôs direct superior, even though she off and on worked together with him. It is clear that the author was very fond of Adam von Trott zu Solz (maybe a bit too fondôthe man had wife and children). In any case, they were very close friends, and the author was, obviously, Trottôs confidante. They dined together, spent evenings talking (discussing developing plans to overthrow the Nazi regime), and the author spent occasionally the night at Trottôs apartment (where he lived alone, as women with children had been evacuated to the country). The author also tried to save Trottôs life (and I praise her for this), after he was arrested as one of the plotters of the Stauffenberg conspiracy.

The reader never learns how much exactly the author knew about the Stauffenberg conspiracy or whether she might have even been involved in it herself. Even her brother (who edited the book, wrote the foreword and epilogue, and supplemented the book throughout with historical amendments) never learned, as he states in his epilogue. Yet even the incomplete information about this conspiracy (and its horrific outcome for those involved) is fascinating enough to make this book a must-read for everyone interested in this subject, and I might even reread this part of the book at some time.

The descriptions of the terrible impacts of carpet-bombing as well as the authorôs narrative about her experiences as a nurse in Vienna (while still dining in first grade hotels with champagne flowing) and her adventurous railroad travel to the relative safety of western Austria (and still visiting aristocrats at castles) when the war was about to end, were also quite impressive and informative. However, one might find similar descriptions and narratives elsewhere, in better books.

The epilogue, written by the authorôs brother, could have enhanced the book, but left me disappointed.

The authorôs diary entries stopped abruptly on September 17, 1945. Naturally, the reader would to know how her life went on and what happened to those people frequently mentioned in the diary who had survived the war. The authorôs brother shows bad judgement by writing half a page describing the Russian orthodox rituals of the authorôs wedding (surprisingly with a commoner, whom we learn very little about). But then, the authorôs brother only spends a line or two telling about the accidental deaths of quite a number of the authorôs close relatives and friends without giving the slightest details about these accidents. There are many other things, I would have been more interested in than the rituals of a Russian orthodox wedding. There is not a word about the relationship between the author and her future husband (who is not mentioned in the diary and whom she married only four months after the last diary entry). Neither is there a word about the marriage and whether it still existed when the husband died (away from home), only middle-aged. The epilogue did tell some about the life and fate of people the reader of the diary would have become interested in. However, it was my impression that the authorôs brother was fed up with the job to get this book to market and, therefore, just regurgitated a few pages of thrown together sentences for the epilogue, which left the reader wanting.

Summa summarum: A miserable piece of literature with highly interesting parts about the failed Stauffenberg plot. Also a highly interesting social picture of how the European aristocracy lived even in the worst of times. Yet the latter was, surely, unintentional.

P.S. If you have ever wondered why the Russian Revolution had happened, the lifestyle of European aristocrats, as portrayed in this book, might give you the answer. And if you should happen to have a little knowledge of the German language, go to the following link and see how aristocrats were addressed in Germany. Such addresses were, obviously, intended to secure the superiority of aristocrats and keep commoners ôin their placeô.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anrede

I have no idea about the etiquette requirements to address aristocrats in Czarist Russia, but I assume that they were similar to German etiquette.

P.P.S. If you wish to learn what it was for non-aristocratic, non-Nazi people to live in Berlin during WWII, read Heinz Kohler's brilliant memoir, "My Name Was Five". Here is the link to my review of this book:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...aristocracy diary ww264 s Chrissie2,811 1,446

I was hesitant to choose this book. I was worried that I would be put off by snobby views and the luxurious lifestyle I was expecting of the main protagonist - a Russian princess. Wouldnôt I find the abundance of privileges in comparison to how others were living unpalatable? The author was not snobbish! Yes, they did sometimes eat oysters and caviar and drink champagne, but she was intelligent and well-educated and perceptive of others. Her friends and acquaintances were interesting people to learn of. Her experiences were worth sharing. Some were wonderful ô a wedding. Some were simply horrible ô the bombing of Berlin. I felt I was there in both instances.

What drew me to this book was I wanted to know more about the July 20th plot to kill Hitler. She worked with and knew the people involved with this plot. It is fascinating to watch the events unfoldô and horrifying to read of its consequences. This book is not your typical holocaust book on WW2, but it is just as important to read this as those books if you are looking to understand what happened in WW2. And I promise you, you will be there during the bombing in Berlinô ô .

Fascinating people and fascinating events told in a riveting manner. I highly recommend this book.

I listened to the audiobook version. The narrator was so calm! This fit wonderfully to its being a diary. The calmness added strength to the words.

Only one thing bothered me. It seems strange that she was so tightly aligned with the people involved in the plot. How did she escape unscathed? Would one dare to write what she writes? Wouldnôt this be too dangerous? I know she wrote in a disguised script, but stillô . Is this truly a diary? How much of it was written after the event? It is stated that her brotherôs thought and explanations are added, but that she did not alter her diary writings when the book was to be published. Still, I am a bit skeptical.2012-read audible-us bio ...more21 s Sue262 36

Berlin Diaries, 1940-1945, is an amazing WWII diary of an ûˋmigrûˋ Russian princess who was secretary to Adam von Trott, mastermind of the unsuccessful 20th of July plot to assassinate Hitler. Missie Vassiltchikovôs account of Berlin in the furious days of Hitlerôs retribution is unique. While she was not part of the plot, she knew many of the principals. Her familiarity with many of the plotters no doubt gives this book great historical importance, and it is also an excellent source for understanding the war from the standpoint of German civilians. She began the diary in January of 1940 when she went to Berlin to look for employment, and she continued through the end of the war.

I am really in awe of this woman. She did not write the diary for publication,which came many years later, when she was adamant about not editing out the bits of trivia or parts which might be unflattering to its characters. She understood that if it was to have value, it had to be the straight report she put down while life was falling apart around her. So we also have reports of meals and hair stylings and bottles of champagne.

As an aristocrat, Missie had unusual opportunities through her aristocratic friends and circumstances ô hence her level of suffering was different from that of the ordinary German citizen. Itôs impossible to ignore the bits of privilege she enjoyed, but this was, after all, a diary. It was never intended as anything but a personal record, and Missie is not trying to speak for all German people or for all civilians. She only reports her own life, and she ended up in Berlin because she could get a job there. A stateless person with a Lithuanian passport, she knew of no other place in wartime Europe that would provide the possibility of a livelihood. Yes, she had some privileges ô mostly the availability of a large circle of other aristocrats whose homes were open to her when she needed companionship or shelter. But she never complained, she had no money except what she could earn, and she rose to meet the challenges. And so we encounter the bombs, the hunger, the cold, and the fear. But Missie could hardly bear to be away from Berlin, where the intensity of history compelled her more than the safety of the countryside.

I found the aristocratic circle of friendship actually very intriguing as a sub-theme. This book has most value as an eyewitness to life in Berlin during the war, but it also provides a glimpse into a world of landed estates and titled wealth. Itôs difficult in the US to have a real perception of what that dying world was .

A wonderful and astonishing read.18 s Ed 479 33

Four stars for the printed book, five for the Audible edition.

The text against which all historical or literary diaries in English (written in English or through translation) must be tested is Samuel Pepys "Diary", the three thousand page plus behemoth covering 10 years of the life and times of Pepys, a successful civil servant under the Stuart monarchy. He listed his meals, his walks through London, the administrative duties he undertook and his obsessive pursuit of sex for a decade. Marie Vassiltchikov's Berlin Diaries 1940 - 1945 is in the vein of Pepys's but since she is a less interesting and perhaps more reticent person her book suffers in comparison. But only in comparison to the 17th century masterwork of daily observation.

Marie Vassiltchikov wrote what she saw, heard, smelled, tasted and less about what she felt. She was a princess back in the old country, a stateless refugee with excellent language skills and a very eclectic group of friends (Count von this, Graf von that) in Berlin. She used the same emotionally blunted, affectless prose style whether describing a ball at the Chilean Embassy, a day at the English language section of the German state radio corporation or bundling with her sister in an ice-cold bedroom to keep from freezing. Even when she describes the carpet bombing and resulting firestorms in Berlin she sticks with her "just the facts, ma'am" prose.

Casual readers of Russian literature ,which includes me, often have problems with the various names, patronymics, military ranks and noble titles often used in various combinations to refer to the same character. In ôAnna Kareninaô for example, an unfaithful husband is referred to as "Stepan Arkadyevich", ôOblonskyô and his diminutive ôStivaô. He is also a prince and as such does he outrank Alexey Kirillovitch Vronsky, a mere count? And if Prince Myshkin were to wander over from Dostoyevsky where would he rank? In ôBerlin Diaryô the titles are thrown around cannonballs in ôWar and Peaceô but are possible to figure out who or what they are since they have context that is missed in novels; perhaps it is less important in imaginative literature.

Vassiltchikov is indeed a princess, perhaps a royal princess although with the Bolsheviks in power that wouldnôt get her far in Moscow. What seems to be important is that her family was wealthy, real haute bourgeoisie with villas here and dachas there, a farm in Lithuania and had enough capital to finance a life style fitting their station. This was lost when the Red Army rolled into the Baltic States and eastern Poland and then when the Nazi blitzkrieg overran the same territory, but Marie and her sister Tatiana (who is in many entries of the diary) hung on to their wealthy and influential contacts, particularly diplomats from pro-Fascist or at least anti-Republican nations such as Argentina and Chile, both of which support the fascists of the Phalange led by General Franco in Spain.

Penniless, attractive and unattached women many have been thick on the ground in Berlin at the time; throw in (at least according to the pictures in the book) an unmistakably aristocratic mien, ability to make small talk in several languages and a two-for-one dealôinvite either Marie or Tatiana and the other one is almost sure to show up as well. Invitations were not lacking both to embassy parties around town and a stream of house parties at the stately homes of the wealthy and titled. The parties stopped when the RAF and United States Army Air Corps began daytime ôprecisionô bombing and nighttime saturation or carpet bombing.

Vassiltchikov came into her own as a reporter/diarist during the campaigns of 1943 and 1944 both in her riveting description of the damage done to what seemed to be every building in Berlin and also her observation, confirmed by the Strategic Bombing Survey conducted after the war, that despite the devastation and destruction the morale of German civilians and their willing to continue working never ceased. It was much London during the Blitz a few years beforeôboth Londoners and Berliners, at least those who couldnôt leave town, took shelter, dusted themselves off and went back to work.

Vassiltchikov knew many of the members of the conspiracy which carried out the July 20 plot, an attempt to kill Hitler, seize the reins of government and negotiate some type of surrender with the Allies. We will never know if the negotiations would have worked since Hitler survived due to a bit a bad planning and a lot of bad luck. She writes of her attitude toward the plot, that she was only interested in the ôelimination of the Devilô and not in the government to be formed afterwards. As a Russian, Hitler dead was enough for her. She and one of her female friends walked into Gestapo headquarters to seek information about acquaintances who had disappeared after the failure of the assassination and going repeatedly to the Lehrterstrasse prison and ingratiating themselves with guards in an attempt to get messages and presents of food to their imprisoned friends, all of whom were executed.

She escaped the fire of Berlin and into the frying pan of Vienna in 1945 where she served as a nurse at a woefully underequipped hospital and living through more mass bombings as the Allies turned their attention of the Austrian capital. This is described with the same attention to detail as he bombing of Berlin a year earlier. She stayed one jump ahead of the advancing Soviet forces when the entire hospital was evacuated to the Alps. Her war ended when the American Army liberated the area.

A note the style of the Audible edition, much of which I re-listened to over the past few days: the narrator, Alexandra OôKarma (a enchanting name) hits the character and expressions of Marie as perfectly as I can imagine anyone doing soôit is a real delight.11 s Kristin59

Final review: i remember why I loved this book. Her ability to communicate the excitement, anxiety and fear during these war years is absolutely unparalleled. And the inside story on the plot to kill Hitler... And she does it all through unselfconscious diary entries and letters. Loved this book.

I'm about halfway through at this point, and just loving it. I read this book when I was in college and remembered that I had really enjoyed it. Now I remember why. I'm not a huge non-fiction reader so things have to grab my imagination. One of the first things that helps me with this book is the lack of footnotes--I despise footnotes and endnotes that destroy the rhythm of a book. This book is written with the author's diary in "regular" font and the comments and notes from her brother (her editor) in italics after relevant paragraphs. LOVE this style. Please take note all you footnote addict authors!

On to 1943...

9 s Patty549 7

This is difficult. I love this topic and was quite prepared to love this book. The author was a White Russian whose aristocratic family escaped Stalin's terror and fled to Germany just before World War II. She was part of a crowd that was linked to the ill-fated July 20th attempt to assassinate Hitler. So, everything was is place for the perfect book. Not so. Until the actual attempt on Hitler's life, the diary entries are slogs through a catalog of the aristocracy of Eastern Europe and Germany, Austrian and Italy. There is lots of champagne and plenty of oysters between horrific bouts of Allied carpet bombing. There are sad storied of having to leave behind one's furs or crystal or.... What is missing is a real connection to all these people or any real feelings at all. It is a list- of aristocratic play pals, of castles for weekend visits, of dining and dancing, of bombed out houses and streets. That said, the book does get more interesting, perhaps because the author herself seems more invested emotionally in the horrors of the Nazi response to the attempted murder of Hitler. There are some few side notes that were quite resonant- the lack of foresight in the demands for "unconditional surrender" which may have prolonged the war, the refusal of the Allies to deal in any significant way with the rather large group inside Germany determined to stop Hitler, the apparent Allied attitude that all Germans were the same and all were complicit in the Nazi terror, and the devastation the Allied bombing had on the civilian population of Germany- ironically missing all the munitions factories for which they were supposedly aiming. Having read about the V bombs and the Blitz directed at London, I am not sure the author (or rather her brother who writes the comments between the diary entries) can really claim much moral high ground. I am not sure there is any such thing in war. Thus, the second half of the book is more interesting and would make an intriguing discussion for a history class. In fact, the last third is very interesting, but still plagued a bit by all the names of people we don't know or care about.non-fictionhistory8 s Charles Mccain18 3

In my research for my novel, An Honorable German, this was an indipensible book. The reason: the rich detail Missie recorded about her daily life in Berlin including what it was to live in the city during the years it was constantly being bombed. This is one of the few contemporaneous diaries from that time. She was a beautiful White Russian Royal Princess, as she reminds us several times, and kept up her active social life amisdst the slow collapse of Berlin. In doing so, she recorded details which can seem girlish and flippant now since she mainly writes about how the war is making her life social life difficult. But the information one gleans is invaluble: hats werenôt rationed, she played ping-pong, a staple of life was macaroni. For all the fascination I have with this diary there is one very unsettling fact: she worked for some months as a secretary to one of the key conspirators in the 20 July 1944 plot to kill Hitler yet is never interrogated by the Gestapo at least she doesnôt write about it. Did she rat someone out? Perhaps we will never know but donôt believe everything she says about herself.6 s Sandeep Chopra35 2

This book offers a unique and extraordinary glimpse into the life of the people during those terrible and unforgivable air raids made by Allies. The terror, hopelessness, confusion and dismay comes through very well in the lines Missie penned down in her diary, day after day.

Her writings touch beautifully on the days immediately after the failed July 20th attempt on Hitler and how the purging process spread fear amongst the plotters, even those remotely connected with the plot had a lot to fear - sometimes more than the bombs raining down.

At times, Missie goes into a ramble and that gets boring and drags. However, I guess we can forgive her for that and maybe cast an askance glance at her brother who, I guess, was the chief editor.

Overall a good read for those who are fascinated by the life and times of the German people during the war. 5 s Suzanne20 1 follower

A day to day account of an exiled RUssian princess during WWII in the middle of the hell Berlin was 1940-45. Also is such an interesting perspective because she was attending royal functions and rubbing elbows with lots of dukes and duchesses while starving and working as a secretary. She also was involved in the anti-fascist scene, friends with those who tried to kill Hitler in 1943. Typical day: work for the SS office as secretary, walk home through burning Berlin, find an invitation to some royal function so as to procure dinner, hang out with commie friends, go to bomb shelter during nightly raids. Nice to read especially since I am living here in Berlin and can visualize each street etc.5 s Positive Kate60

This book was a diary that involved many people that Missie knew. At first the book was a documentation of her social friends going out every night, but then some of her colleagues were involved in the July 20 plot. Suddenly the diary is amazing, but then three months are missing. Her struggles at the end of the war showed what life was throughout Eastern Europe.This entire review has been hidden because of spoilers.Show full review5 s Andey Hix2 2

Exceptional. As I read this book, I realized I was reading slower and slower because I did not want the book to end. Small details of civilian daily life in Berlin--that you don't usually have an opportunity to read about--filled this book. 5 s Brendan Lyons16 1 follower

I thought I had made a mistake when I started reading this diary: date, three or four sentence entry; next date, another short entry; another date, another short entry, etc., etc.

This is definitely not a literary work, as such. It's just a record of what happened every day. What sets it apart from most other works of its kind is that the author ("Missy") a young exiled White Russian aristocrat more or less exiled in Nazi Germany has to make a living and deal with events as the war becomes ever more menacing, encroaching on the personal lives of herself and her sister Tatiana and their wonderfully large and diverse circle of friends and relatives, who seem to be fighting or suffering on all sides in the war.

As the diary progresses it takes hold. It is not retrospective, written at leisure in hindsight: it's a record of the war in triumphant and then losing Germany day by day as seen from the eyes of an apolitical young woman. She obviously doesn't the Nazis but she works for a branch of the Foreign Ministry and s some of her bosses and hates others. She's a moral person feeling rather helpless in a crazy upside-down world who just wants to get on with things. Her male acquaintances from her former life are in the German, French, British, Italian and American armies and she just hopes they'll all survive the madness. Obviously, some don't. She grieves the death of one young friend, a Luftwaffe pilot who shot down 63 American planes. He was no Nazi, in fact he wanted to kill Hitler, but just got caught up in his role in the war from which there was no escape -- except death.

Missy gets caught up in the conspiracy to kill Hitler which failed after the bomb attempt on July 20, 1944, after which the arrests and widening circle of executions began. This is probably one of the best first-hand records of that time that exists. And the bombing: few people remember or even realise that 600,000 people lost their lives in Germany compared to 62,000 in Britain during the Blitz. 4 s Michelle143 4

What would a White Russian do in Nazi Germany during WWII? Other than drink impossible amounts of champagne and carouse with various Counts and Dukes? Plot to kill Hitler, of course.

A strange and bewildering account of wartime Berlin. Hilarious at times, also scary and sad. Read it for the stories, not the writing.4 s Rick197 21

Once you put aside any negative visceral reactions you may have to the extreme privilege that the author had as an attractive young noble, this book/diary makes for a fascinating read and an interesting portrait of life in Germany during WWII. Having mentioned her privilege, which is obvious in the many dinner parties she attended, her hobnobbing with people at the highest echelons, the rules she was allowed to break, the special favors she was granted, and the fancy estates she visited on a remarkably frequent basis, it is important to note that she also effectively chronicles the many privations imposed by the war. And of course one must presume that however bad they were for her they were infinitely worse for the average person. What always fascinates me is the the extent to which daily life often goes on even in the middle of complete chaos and violence and she captures that well here.

I also found the insights this book provides into the lives of the nobles to be very interesting ô how broke many of them were but how little they let it affect their socializing; how interconnected and intermarried they were so that national allegiances could get quite complicated within a single extended family. For example, you might have Germans who are not that distantly related to an American or a Briton. In addition, the circle in which the nobles traveled was sufficiently small that it led to a lot of coincidental meetings in seemingly random places, making the Germany of that time seem a very small place.

Other observations: I never fully appreciated the extent of the damage done by allied bombing, nor did I know how many foreigners were in and out of Berlin during the war and how much flouting of the rules occurred even in this very rigid society.

I also didnôt know how different the concentration camp experience could be depending on where you were sent, your position in society and your national origin. I was astonished at the number of privileges her cousin had where he was interred.

Finally, I struggled with what to make of the authorôs role as an employee facilitating the leadership of the German war effort and her naû₤vetûˋ about the war for much of its duration. Her insights into the attempted assassination and overthrow of Hitler (the planners of which she was close to and d) was very interesting even if she obscures the extent to which she did or did not know of it in advance or actively participate in it.

Some will also be put off by the breathy ôDear Diaryô feel of the book; the authorôs youth is extremely apparent throughout, but these first hand accounts provide windows into the time that the regular history books rarely can and never do as vividly.3 s Daniel HilandAuthorô 2 books4

This is either a wonderful book to read, or a bore, depending on what you .

For history buffs, it's a treasure trove. Marie's journal entries are interspersed with historical annotations (made many years later by her brother George). Italicized, to set them off from the diary entries, they add perspective and illumination to the things Marie is describing. There are maps in the front, 16 pages of photographs near the volume's midpoint, and a detailed 10-page index at the end. But for those of us more interested in a story representing human drama behind the scenes, it's tough sledding.

As for Marie's writing, it's lively and loaded with wry comments and observations on human nature. Many of her entries turn into little tales of their own. Of course, being a diary, the repeated references to parties and club visits and other get-togethers- and there are a lot of those- get tiresome in a hurry. Culling some of them would not have risked credibility or perspective. But that is the risk one runs when centering an entire book on journals.

As I commenced reading the book, I felt whipsawed between the narrator's daily life and the commentary. While I can appreciate the the intent and effort expended to instruct the reader, I didn't care for the interruptions to the flow. Don't get me wrong: the annotations are chock-full of fascinating information and insight. And they are well-written. But the fact that many of them drifted into narrative territory caused me to wonder if a better book could be fashioned from the material.

How about creating an account that seamlessly meshes George's ably-crafted commentary with Marie's entries (the latter written in memoir style). Include a genealogy chart or two, as well as some more detailed maps. That way we'd get a better sense of the family relationships, locations where trips and vacations took place, etc., without having to be constantly interrupted. And that, in a nutshell, describes the limitations inherent in a book full of journal entries.

As I said at the outset, this is a great history book. And though I'm not a history buff, I will return to it again as a reference for WWII events. As a story, though, it's lacking the structure necessary to make it compelling to a potentially wider audience. Some day I'll need to go through the book and cross out all the annotations. Then it will be a more enjoyable read. 3 s Simon841 106

This is not a great diary. Either from self-preservation or a personality issue, Vassiltchikov refrains from introspection as she chronicles life in the wartime Berlin. She was a White Russian refugee, born on the cusp of the Russian Revolution. Her family was part of what might be called the "HMS Marlborough" crowd, the aristocrats who escaped on the coat-tails of the Dowager Empress when the British navy rescued her from the Crimea in 1919. After the Russians invaded Lithuania, where the family wound up, she and her sister Tatiana fled to Berlin, where they were assigned work in the Foreign Ministry. Tatiana married a Metternich and dropped out of the workforce, but Marie stayed until the end. After the failure of the July 20, 1944 plot to kill Hitler, of which she had peripheral knowledge as an aide to Adam Trott, Marie sought to leave her ministerial work and finished the war as a nurse in Vienna. After the war, she married an American soldier. He opened an architectural firm in Paris, where they lived until his death. At that point Marie left for London, where she edited her diary entries for publication until her death in 1978.

She has no literary style, un Klemperer in I Will Bear Witness, and un Anne Frank, one cannot chart personal growth through her entries. What Vassiltchikov has achieved is a record of what it felt to be young, beautiful, aristocratic and in the belly of the beast. She endures the Allied bombings of both Berlin and Vienna with remarkable aplomb, and manages to careen between starvation and feasts with some regularity. The idea that the aristocracy of Europe really was a transnational community is on full display. Aristocrats were regarded with suspicion by the Nazis before July 20, and since so many of the conspirators who were involved were members of the class, with outright hatred after it failed. Numerous princes, counts and dukes are mentioned in her diary as having been forced from the service. Her own brother, as a ci-devant Russian prince, does not participate in the military, despite Germany's undeniable need for soldiers. What do they do instead? They get higher degrees at universities all over Europe, live on their country estates in a manner largely untouched by the conflict, and have princely weddings --- which Marie attends.

It is an interesting read, because of where she was and what she was.3 s Bob2

The diary writer, Marie Vassiltchikov, provides an eyewitness account of life in Berlin during the years identified in the title. That alone is fascinating. She spends a lot of time in shelters to escape Allied bombing. It's very interesting to read about how ration tickets worked, what the job market was , the extent of disruption of daily life, the soldiers' trips back and forth to the front, her escape from the advancing Soviet armies as Germany and Austria collapsed, etc.

If you want deep-thinking about the horrors of the Nazi regime, you're not going to find it here. There are, honest to goodness, more entries about hair-care styles for bomb shelters than there are expressions of concern about the fate of European Jewry. Her problem with the Nazi regime had more to do with the fact that the Nazis posed a risk to her social class, and the fact they were losing the war, than anything else. One of her relatives provides the annotations in the book. His viewpoint is interesting--he spends a fair amount of ink criticizing the effect of Allied bombing on German citizens.

In her defense, there isn't much self-pity, and she's always eager to get back where the action is--Berlin--rather than hang out in the bucolic spots outside the capital where her job and friends regularly take her.

I definitely recommend reading the book. If you enjoy this book, I'd also recommend The Orientalist, which is about another refugee from the Russian Revolution hanging out in Germany during the war.3 s Boyd91 45

I hadn't heard anything about this book before I bought it, and I picked it up mostly because I thought it might provide an interesting preamble to another striking diary I'd read some time ago, A WOMAN IN BERLIN, set in the city in the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion. It did that--I learned that Berlin and its residents were pretty much destroyed long before the Russians got there--but I found it fascinating in its own right because it focuses mainly on a section of society, the European aristocracy, that doesn't often appear in chronicles of World War 2 deprivation. It's surreal to witness these people's slow descent into chaos even as they cling to markers of privilege in the classic fiddling-as-Rome-burned manner. It's easy to laugh at them as they swill champagne in bomb shelters, decide whether or not they feel going in to work that day, and approve of themselves for wangling special treatment through their connections. But it's also hard not to sympathize with them in their bewilderment over what has happened to their rarified lives, or with the many true hardships they had to endure. After all, they'd lost everything, or nearly everything, just everyone else. 2 s Relstuart1,202 106

The diary of a girl from a white Russian family (the white Russians were anti-communists) that fled Russia after the Reds took over. They initially went to Lithuania but then fled to Germany to get further away from the Russian sphere of power. But they could not out-run the war. The author ended up working for the diplomatic corps as a translator since she was fluent in several languages. She knew and worked with several people involved (and executed because of) the plot to kill Hitler. She provides glimpses not only of some of the mid level power people in Germany but also of what it was for ordinary people who tried to make do with the bombing and the somber mistrust of a society where free speech is prosecuted if it does not agree with the party line. She survived many bombing raids and talks about how it impacted the ordinary folks and the people around her that died and the cites that were devastated around her. Towards the end of the war she ended up working as a nurse.

If you are me, all her talk of food and starving will make you hungry while reading this one. folio-society memoir world-war-ii2 s Tomi1,213 8

The diaries were kept by a White Russian emigre who lives in Berlin and Vienna during WWII. She was involved with many of the people who tried to kill Hitler - the Stauffenberg Plot. Her diaries give a very different picture of wartime life; most of what I have read depicts horrible conditions, starvation, death, and just general misery. This woman was an aristocrat and lived a much more pleasant lifestyle. Parties and dinners every night, trips to country estates, new hats on a regular basis...yet she still suffered. She and her friends had problems obtaining food and many of her friends were injured or died. This was another take on life during war and was very interesting.2 s Ruth118 17

Okay, I lied. I did not finish this book. It is a diary, indeed. Of a woman who seems to be not too bright. It is interspersed with italicized bits to give the reader some idea of what is going on in Berlin. From 1940-1945! You would think Marie would have a lot to say, and she does--about dinner parties she went to with Count this and Baron that. She is a terrible writer. It's kind of reading a teenager's diary: I went; I did. I would never have tried to read this idiotic book were it not for the high ratings on GR. If you want to read something virtually meaningless, try another book; any other book at all. 2 s DenisAuthorô 5 books22

The diary of a Russian exiled young woman who lived in Berlin during WWII. Extraordinary and mesmerizing. Witness History through the eyes of a young girl who slowly discovers the reality of the world around her, and survives the horrors of war (while losing many of her closest friends). it's a true diary, and day by day, year by year, it takes the reader on an intense journey through the darkest time of Germany's history. The apocalyptic ending is breathtaking. Nicole Kidman bought the rights of this book at some point - it could indeed made a beautiful movie.2 s John Mccullough572 43

A real look at how one survives in high circles when one is not necessarily in agreement with the "program." A Russian princess living in Berlin during WW II, she was a friend of some of the plotters against Hitler, but was spared. Also, a good lesson on attacking civilian populations - don't because it just angers them and, in this case, prolonged support for the war. Well written, sometimes exciting!2 s Saira165 7

I wanted to love this more than I did. It's definitely an interesting perspective and its pretty neat to get details about civilian life (at least this particular class of civilians) during the war. I just didn't care for how the flow of writing was interrupted by the historical comments inserted between diary entries by her brother. If they had added those in the beginning of each year/chapter it might have been better. For being a diary, I also expected a little more emotion. 2 s David351

I read this in the late 80's. It was common person's perceptions of what was going on all around her. A mix of slice of life and historical witness. It gave me an idea of what it was to live in a city that was constantly being bombed. While she did not support Germany she did have German friends. own2 s V14 1 follower

An incredible view of WW2 and the Holocaust as it was happening. Vassiltchikov was able to act as observer and later in collaboration with freedom fighters as they sought to put an end to Hitler's regime. Marvelous perspective.holocaustmemoirs holocauststudies2 s Becky2 2

This isn't just a historical book. Its a diary written by a white russian princess during World War II. A true story it follows her travels throughout the war as she lived and worked in Berlin but continued to live a life amidst bombs, lack of services and war.2 s Eileen11 2

This is a tremendous first-person account of wartime (WWII) Germany, written by a White Russian princess.

Her transition from spoiled post-deb to capable adult is remarkable.

An excellent book, and worth owning.2 s Alec73 3

I love this book. Such an interesting glimpse into life in Berlin during WWII, told from the perspective of a foreign aristocrat. The author notes not only the trivia of daily life but also talks about the times and how they affect her and her life. history2 s Shelley167 1 follower

Autor del comentario:

=================================