oleebook.com

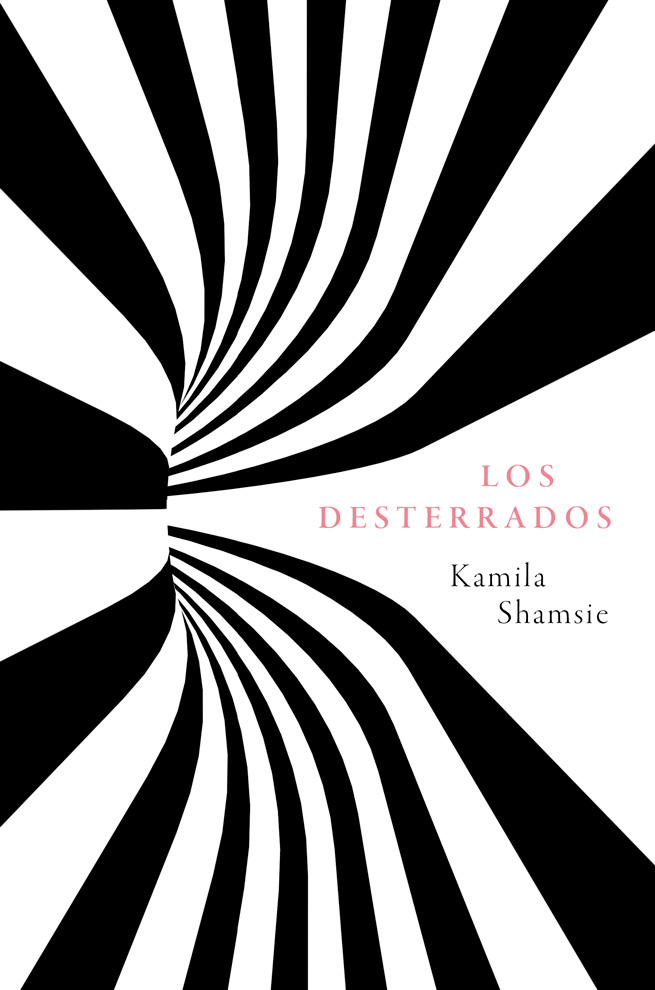

Los desterrados de Shamsie, Kamila

de Shamsie, Kamila - Género: Ficcion

Sinopsis

¿Hasta donde llegarías para salvar a quien más quieres? La historia de una familia atrapada en el conflicto entre Occidente y el Estado Islámico.

Descargar

Descargar Los desterrados ePub GratisLibros Recomendados - Relacionados

Reseñas Varias sobre este libro

Just announced as the winner of Women's Prize for Fiction. So happy the novel finally got the recognition it deserves.

4.5* rounded up.

Home Fire is the candidate I support to win the Booker Prize. Well, I only read 4 nominees until now so it is not a definite opinion. However, it is highly unly that I will make too much of an advancement in my reading of the longlist until the shortlist is published so it will probably remain on top for a while.

If you read a few you will realize that the novel is based on Antigone. Unfortunately, I cannot add anything on the subject as I have no knowledge of this classic story and I would feel a fraud to comment on it after only reading the Wikipedia summary.

The novel is divided in 5 sections, each focusing on the experience of one character. At its core, it is the story of a British family of Pakistani origin and their struggle to live in their adoptive country in the shadow of the terrorist threat, especially because of their troubled history.

I did not ponder too much how it must be for a normal Muslim family abroad to live with all this suspicion from people and the government. This subject has an important role in the novel and it made understand how difficult it must be to make sure that you do everything right, that you do not provoke violence, always being afraid of being followed. It also discusses the difficulties a family faces when a member of the family proves to be jihadi. It also touches IS recruitment and other sensitive subjects that are very well done.

I thought the beginning to be a bit shaky but please persevere. The writing gets much better after 30 pages or so. It becomes a powerful, emotional and important novel for our times.

I received this copy from the publisher via NetGalley in exchange for an honest review.

****

4.5* An excellent book overall although there were some shaky parts. Made me think about a subject I did not pay too much attention: how to live in as a Muslim Citizen of an European country with the potential terrorist stigma. Review to come next week most liekely.booker british pakistan335 s Maxwell1,231 9,815

I don't give 1-star very often because I feel I don't read a lot of books I would label as 'bad.' And this book, even, isn't 'bad' in my eyes. But when I think about things I enjoyed regarding this novel, there's pretty much nothing redeemable for me. The characters were flat, the plot was paper thin (even though I know it's a modern retelling of Antigone, I don't feel that knowledge did anything to elevate the story), and the writing was nothing special and verged on poor at times. I know others who loved this book but, boy, I did not. In fact for the first time in a long time I couldn't wait to finish it. And that never really is a fun reading experience. If it had been any longer I would've DNF'd it. But I was more determined to push through since I am attempting to read all of this year's Man Booker longlist. Wouldn't necessarily recommend this but read some other and see what people had to say that d it, because it might be just the right book for you. It wasn't for me.200 s Larry H2,576 29.5k

Ever since their mother and grandmother died within the period of a year, Isma has cared for her younger twin siblings, Aneeka and Parvaiz. Their well-being has always been her first concern, even if it meant sacrificing her own dreams and ambitions. But now that the twins have turned 18, Isma is finally putting herself first, accepting an invitation from a mentor to travel to America and co-author a paper with her.

That doesn't mean Isma won't worry about her siblingsAneeka, smart, beautiful, and headstrong, is pursuing studies in law, while Parvaiz has left their London home to try and understand the legacy of their father, who was once a jihadist. Isma does what she believes is right, even as it causes a rift in her family, but she is bound and determined that her brother will not follow in her father's footsteps.

"For girls, becoming women was inevitability; for boys, becoming men was ambition."

When Eamonn, the son of a prominent British politician who has struggled with his own Muslim background in furthering his ambitions, enters the sisters' lives, he, too, causes a rift that he doesn't quite realize at first. Who is he to them? Is he a romantic possibility? A chance to enact revenge? The last hope for a wayward brother? The linchpin of a political crisis? Suddenly many lives hang in the balance, as true intentions are sought to be understood, and emotions are analyzed.

What is stronger, blood or love? Can we ever overcome the obligations of family in order to move on with our lives, and if we can, should we? In Home Fire , Kamila Shamsie attempts to answer those questions, as two families deal with the questions of love and loyalty, and how slippery the slope is when we start choosing enemies based on cultural generalizations.

This is a powerful, timely book, and Shamsie does a good job navigating difficult political territory. For the most part, these are interesting characters, and I really became immersed in their stories. I felt, however, the book lost its way in telling Parvaiz's story, for while it was important to the plot, it just wasn't as interesting, and a lot was left unsaid. I also felt that Isma, who plays such a key role at the start of the book, is given short shrift, yet she is fascinating, evidenced by an all-too-short encounter with the politician which seemed it could have developed into more.

Shamsie is a talented writer, and this book is definitely a thought-provoking one about the ties of family and the immigrant experience. While it didn't resonate for me as much as, say, Exit West , it's still a powerful read.

See all of my at http://itseithersadnessoreuphoria.blo....175 s Elyse Walters4,010 11.2k

Update ... WINNER for the womens prize of fiction for 2018!!!!!

SHORT LISTED FOR THE WOMANS PRIZE FOR FICTION

LONG LISTED FOR THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE

WOW!!!!!

Personal and political life merges together in the most heartbreaking of ways when a man loves a woman whose family is connected to a Muslim terrorist.

The author explores justice, love, and passion in ways that can be compared to older classics - think Romeo and Juliet - yet set in modern time.

Beautifully written - poetic - great character development.

Its painful to read about two families pitted against each other...but its very insightful and informative- especially how the ISIS recruits - influences - and corrupts.

Terrific Discussion Book! Diane S ?4,817 14.3k

There are so many timely subjects right now, world concerns and threats, and authors have responded in kind. This novel features two Muslim families in Britain, two families that have very different opinions on family and how to show or display their Muslim beliefs. It moves the themes in Sophocles, Antigone to present times. I remember very little about Antigone, refreshed my memory on Wiki, but I cannot really knowledgeably comment on the adequecy of the comparison.

The novel starts out slowly paced, rather inoculously, as a young Muslim women, who has spent many years raising her two twin siblings. Now that they are old enough, Isma decides it is time to complete her interrupted education. The family!y of three has long been under the surveillance of the British Security service as their father was a known jihadist, who died on the way to Guantanamo.

We learn about the methods used to recruit young people, usually 18 or 19, to the Islamic terrorist cause. The novel is narrated in alternating chapters by the five main characters. Each succeeding chapter is more intense, and by the time we hear from Aneeka, this story had radically changed, become super charged, very intense. The novel displays a confidence not only in prose but in how the story is related, which I found extremely effective.Complex issues. Love of family, youthful mistakes, how much can be forgiven. Government stances versus family, fear versus love, and the difficulties of Muslims, how they must act to fit in with society.

Long listed for the Booker, I find tis a very worthy addition. Unforgettable, some of the visuals displaying a sister's love I don't think I will forget.

ARC from edelweiss.140 s jessica2,566 42.6k

im not familiar with the story of antigone, so i cant comment on how this compares as a retelling. but as a story about family, sacrifice, and identity, this is one to undoubtedly make you think.

which i have. its actually taken me awhile to think about how i want to rate/review this. immediately upon finishing, my gut reaction was 3 stars. its an good story but nothing great. it quite short, so there isnt a lot of development, which leads to a lack of deep connection with the characters, even if they are interesting. so again, its good, but not great.

so why then can i not stop thinking about this?? theres just something so compelling about this story, how its written, how its structured. and dont even get me started on that ending - i think im still in shock. theres just a certain quality to this that makes me want to overlook all of its flaws, a certain quality that makes me feel guilty for calling this a good story when it feels so much more. i really dont know how to explain it.

so if you have a couple of hours to spare, this short, but insightful, book is definitely worth your time.

? 4 stars142 s Hannah Greendale651 3,712

Click here to watch a video review of this book on my channel, From Beginning to Bookend.

adult booker-prize-nominee fiction ...more135 s Jenny (Reading Envy)3,876 3,483

I went looking for a review copy of this when it was included on the Man Booker Prize Long list, and was approved for one by the publisher through Edelweiss.

This is a book that kept morphing as I read it and discussed it, and it ended up in a place far removed from my expectations at the beginning. Nowhere in the publisher summary or promotional material does it mention that the author is also basing this novel on the myth of Antigone, but she has, and that proves important in understanding some of her choices.

The author is from Pakistan, and the characters have some loose ties to Pakistan and end up there during some of the events, but it is more important inside the novel that the three central characters (siblings) are all children of a jihadi who was killed during or because of his military action. The characters themselves aren't certain, just know that he's gone, so I won't give that detail away. It's important to also understand that as a jihadi, he is working toward the magical homeland idea, and to that end has voluntarily fought in Afghanistan, Syria, Chechnya, and beyond. And the people he was involved with have done the same. Between that fact and the fact that the siblings are split between the USA and the UK, and the placeness of the novel feels very unstable.

More instability in the novel comes from the shifting viewpoints and genres. The novel starts with Isma, the oldest sister as she moves to Amherst for school, including a long drawn out inquisition at the airport that makes her miss her flight. She meets Eamonn, son of a powerful politician in the UK, but his family is also close to her family in country and religion of origin, even if they don't seem to claim it anymore. At this point the novel feels it is headed one specific direction, but there is a major shift to a romance novel for a while, and then it turns into a jihadist recruitment novel, and then a story about the placelessness of people labeled terrorists. Too much time, perhaps, is spent on what to do with a dead body without a country (this is a place where the author is trying to hard, in my opinion, to shoehorn the novel into the myth, when it is not needed, she has enough of a story without that.)

As you can tell from my attempt to summarize, there is a lot going on in this novel. But I also found myself thinking far more deeply about the context. How far reaching are the wounds of Partition, which is where this family first lost their footing? How has that impacted the longterm inclination towards jihad? How do the way their family is treated in the USA and the UK effect how one member can only find home and family with a group of soldiers who knew his father? And outside this story, how is our current political situation worsening these kinds of narratives, pushing people into outsider status and otherness, without home, without firm footing? I think that's the thread that is between the lines, and to me, the most powerful part. I was waffling between three and four stars but I think my own thinking as a result of the novel pushes it to four.

I do think there are misses here, though. The mythological connection weakens the story, especially the ending. Without saying what the ending is, I think it's a cop out to have a single climactic moment rather than following characters as they deal with the real-world, complex complications of the decisions that people have made. That's a movie move, not a novel move. There are missed opportunities between characters, conversations and interactions I expected them to have but are instead skipped, glossed over, or deemed not important. Isma and Aneeka should have had a huge fight about one plot element, and I felt the connection between Isma and Eamonn's father had a lot of potential and it just dissipates.

I would to read more by this author, although I personally don't feel this is strong enough to make the Booker shortlist. Too many dropped plot points, a lack of realism at crucial moments, and the unevenness in genre and story arcs. I did appreciate the deep thinking it inspired, and it ended up having enough in it to count as one of the reads for my Borders 2017 challenge.around-the-world booker-winners-and-listed borders-2017 ...more116 s s.penkevich1,125 8,826

Grief was what you owed the dead for the necessary crime of living on without them.

Literary retellings have had a day in the sun the past few years. From simply updating to a modern setting to different points of view to recast the story in new light or toying with a story until it is almost unrecognizable. Kamila Shamsie Home Fire, winner of the 2018 Womens Prize for Fiction succeeds as a modern retelling by expanding both upon the perspectives of a Greek play but also expanding our understanding of our modern racial political climate. It isnt a spoiler to know which Sophocles story Shamsie is updating (the opening epigraph directly calls it out in a quote translated by Seamus Heaney), which is a real credit to her storytelling as the dramatic ending still connects a deeply emotional punch to the gut even though you know what will ly occur (just not how). This book is just gorgeously written and hits all the right notes of anxieties, love, betrayal, and the heroism of one girl standing in defiance to the State. Things are going well for the family until the young brother becomes radicalized and joins an extremist army and suddenly the powder keg of racial tensions is lit and ready to blow. Through modernizations of themes, such as the charmingly clever use of social media as a Greek Chorus, and a rotating cast of narrators each with a unique perspective, Shamsie takes a bold look at immigration, political fearmongering and identity in a post-9/11 world through a riveting story that will have you up all night turning pages.

What better choice for a racial discussion of a modern day Thebes than London, particularly as Home Fire was written and released during the tensions of failed Brexit deals and rising nationalism around the world. The story presumably takes place before (Brexit is notably absent from the list of hot topics Isma is asked when being questioned by Homeland security) but still in the tumultuous post-9/11 political climate of ISIS and rampant (and inherently racist) anxieties over Muslims. Instead of warring families as in Sophocles, Shamsie presents us with anti-immigration politicians and a family whos father was a known jihadist that died in custody. This is similar to the recent film adaptation with Romeo and Juliet being Palestinian and Israeli as an effective way to let modern world traumas form the exposition of tension between the rivals in classic works. Through Shamsie's perfect poetic prose, this update signs with all the strength of a classic yet feels so comfortably embedded in the present.

By the time the first light appeared in the sky she felt herself transformed by the desire to be known, completely.

The story largely concerns issues of identity, particularly when your identity makes you a mark for scrutiny and hatred. The story opens with a tense airport questioning where oldest sister Isma knows any answer not deemed good enough will put an end to her university studies in America, an end to her much desired freedom, and create problems for her already on-the-radar family. For Isma, this aspect of identity is all consuming. Freedom is also a desire of her younger sister, Aneeka, who resists patriarchal society. For their brother, however, he is more driven by a desire to fulfill his father's legacy and be thought of as a man. For girls, becoming women was inevitability, Shamsie writes, for boys, becoming men was ambition. Isma figures herself to be the level-headed role model and warns how easily their world can be shattered simply for being Muslim.

think about those of us with passports that look toilet paper to the rest of the world who spend our whole lives being so careful we dont give anyone a reason to reject our visa applications? Dont stand next to this guy, dont follow that guy on Twitter, dont download that Noam Chomsky book.

Muslim identity is also at heart of the other family in this novel, the family of wealthy MP and home secretary Karamat Lone. Shamsie uses Karamats Muslim heritage to attack the ways politicians are less so people with beliefs of principle than beliefs of convenience. As a younger, rising star in Parliment, Lone used his Muslim heritage to win his base, whom he promptly discarded upon achieving real power. Once hoped to be a champion for immigrant rights, he is now hard-line anti-immigration and said to be Mr. British Values. Mr. Strong on Security. Mr. Striding Away from Muslim-ness. While despicable, Karamat is easily the most nuanced and successful character and the chapter from his POV is a wild ride through self-deception and a cold-hearted logic where the ends justify the means, no matter who gets hurt. Contempt, disdain, scorn: these emotions were stops along a closed loop that originated and terminated in a sense of superiority.

As drama builds for Isma and Aneeka with their brother run away to join the jihadists, Karamat is kicking up racist dog whistles to champion himself in the next election and ride the wave of nationalism and anti-Muslim sentiments for personal gain. I hate the Muslims who make people hate Muslims, he says, in the sinister politician way where he can never be hung on his words and knows he can backtrack if pressed. When the inevitable happens, suddenly there is a dispute over if a body can cross borders for burial and both families are enveloped in scandal.

At its core, this is a love story wrapped in politics. Familial love and romantic love are the beating heart pumping this story along. For, unbeknownst to Karamat, his son Eamonn has been having a hidden relationship with Aneeka and now their personal lives are the talk of the media. With love, however, there is always the risk of betrayal. Through the rotating perspectives, we witness the relationship from multiple angles that keep you guessing if it is authentic or for political gain for Aneeka, while also watching Isma feel betrayed by her sister for sleeping with Eamonn when she had her eye on him in America, and by her brother for his actions. There is also the betrayal of your adoptive country who is quick to turn on you and label you a terrorist. Each new perspective expands the drama and also illuminates previously unlit corners of earlier events as Shamsie brilliantly fleshes out the story in a way that keeps it fresh in tone, voice and actions.

What translates best in this adaptation is the power of defiance in the face of the State. Aneeka not only single-handedlyand very publiclystands up to and actively disobeying the State but she makes its own players complicit and forces their hand. Karamat seeks to be a man of principle, but is currently under scrutiny for his waffling allegiance to his heritage, and Aneekas actions must make him publicly stick by his word and thus create scandal or give in to her singular wishes and tarnish his already fragile reputation (also a healthy dose of scandal on this option still). It is a thrilling and moving act that shows how one person can make or break on a mass scale.

One of the most effective parts of the story is the twitter posts, news reports (both national news and tabloids) that are interspersed with the narrators. It not only grounds the story in the present but also serves as a sort of Greek Chorus to comment on the moralities of the tale. It also functions as a commentary on how, with social media, we often act as readers of national and international events, even participants (an unverified tweet sets off a chain reaction of events late in the novel). It serves as a good reminder that even the personal can be political and how we tend to all rally around a side whenever a story begins trending.

Even if the reader is familiar with the source material, the ending is still highly successful. Shamsie has crafted a novel that is so infectious that I read it over a weekend and spent any time away from the novel thinking it over and yearning to get back. It is highly cinematic, which gives it a fast pace, though slowing it down and letting it breathe would have been welcomed rather than going from event to event. The sections of Paraviz becoming radicalized are especially intense and Shamsie shows that emotional manipulation is often the tool for any army to get someone to die for their cause. Love and betrayal go hand-in-hand here, but, despite how things turn out, Shamsie reminds us that love was still the victor. Timely, insightful, poetic and irresistibly engaging, Home Fire is a book I find myself telling people to read all the time even two years after having read it.

4.5/5

Everything else you can live around, but not death. Death you have to live through.109 s1 comment Paromjit2,864 25.3k

I have written and lost my review for this on Goodreads, I will try and rewrite it again, but am currently overloaded. However, this is my book of the year although it has taken a long time for me to get round to reading it. A remarkably accomplished novel inspired by Sophocles Antigone, with its profoundly moving and heartbreaking tragic examination of the fate of 2 British immigrant families that resonate deeply with recent history and our contemporary realities that I do not think I will ever forget. Absolutely incredible, if you have never read it, I strongly urge you to do so.family-drama literary-fiction109 s Hugh1,274 49

When the Booker longlist was announced, this was one of the books that most interested me, because I really enjoyed Shamsie's previous two novels (A God in Every Stone and Burnt Shadows). I was a little nervous when I read that this is a modern retelling of Antigone, because my knowledge of the classics is very limited, but it is a fine book and another one which would make a worthy winner.

The book is in five sections each of which focuses on a different character. I found the first slow going - we are introduced to Isma as she travels from Britain to Massachusetts to pursue her academic career. Isma is an orphan who has been looking after her younger twin siblings (Aneeka and Parvaiz), and her father was a jihadi fighter in Chechnya and Afghanistan who only returned occasionally. She meets another Briton from a Pakistani family, Eamonn, who is the son of the home secretary (Karamat) and is in America on holiday. This section is primarily a scene setter - the real action starts when Eamonn returns to London and meets Aneeka. They embark on a clandestine affair.

In the third part we learn more about Parvaiz. He is a drifter more interested in sound recording than working who is left at a loose end when Isma leaves for America and Aneeka starts a law degree. He gets entangled with, and radicalised by Farooq, who turns out to be a recruiter for IS and who persuades him to head for Syria, with the promises that he will find out more about his father and his death while being transported to Guantanamo, and that he will lead a privileged life in the media arm of the organisation.

Things heat up when Parvaiz decides he wants to return to Britain, and the remainder of the book plays out the tragedy that ensues. It transpires that Aneeka's interest in Eamonn was initially motivated by the idea that he could help her twin brother. When Parvaiz is killed in Istanbul, it is decreed that his body cannot be returned to Britain and instead it is sent to Pakistan. Aneeka goes to Pakistan to fight to have the body returned, and this mirrors the original Greek tragedy.

I won't comment in detail about how this relates to the Sophocles play or the Anouilh version of the story - I will leave that to more expert critics. What I will say is that as a modern parable it works surprisingly well and becomes a very compulsive story. The Prime Minister and Chancellor are obviously modelled on Cameron and Osborne, so it is clear that Shamsie did not foresee the upheavals of the Brexit vote, but all of the other political content is chillingly plausible, and Shamsie paints a very nuanced picture of the difficulties faced by the Muslim community in dealing with their own extremists on one side and intolerance and misunderstanding on the other.

Perhaps slightly flawed in places, but the best parts are very good indeed.booker-longlist modern-lit read-2017 ...more90 s Dianne575 1,149

This is a powerful and gut-wrenching book loosely based on Greek mythology's story of Antigone, a woman defying a king to secure her brother an honorable burial. I knew this going in, so I did some research on Antigone so I could appreciate the parallels as they unfolded.

"Home Fire" is told through 5 viewpoints: sisters Isma and Aneeka, their brother Parvaiz (Aneeka's twin), British Home Secretary Karamat Lone and his son Eamonn. Isma, Aneeka and Parvaiz are Muslims living in London and Amherst, the children of Adil Pasha. Adil abandoned his family to join the "fight against oppression" as a terrorist, and after imprisonment in Bagram, died on a plane for transport to Guantanamo. Being the children of a known terrorist creates difficulties for Isma, Aneeka and Parvaiz that play out in various ways throughout the narratives.

This is a classic Greek tragedy in a modern "of the moment" setting, both heartbreaking and eye-opening. I deeply appreciate Shamsie's ability to create empathy for each character and their situations. This was long-listed for the Man Booker in 2017 and was the favorite of many of my Goodreads friends, and for good reason.

I highly recommend this gem. Also, here's a shameless plug for another Antigone-based book that I loved, "The Watch" by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya. Not as masterful perhaps as Shamsie's, but one that deeply affected me and I still think about often.best-of-2017 booker-201784 s Dem1,214 1,277

A remarkably short Novel that delivers on an epic scale. A story of family ties, loyalty and a story of prejudice in the modern world. A thought provoking and intelligent novel that left me wanting to read more of Kamila Shamsie's work

This is another one of those books upon finishing I cant help regretting I hadn't read this as part of a group read just for the discussion factor as there is so much to discuss.

The Novel has a very powerful opening wih Isma a Muslin woman struggling to be admitted to the US on a student visa and her long delay in the interrogation room results in her missing her flight. Isma, Aneeka and Pavaiz have had nothing but each other for a long time, Their father's past rears it's ugly head and Parvaiz gets drawn into a world that nightmares are made of.

I loved the structure of this novel as it tells each character's story from his or her point of view in separate chapters. This is a brave novel and certainly makes you think, its well written and the characters are believable and interesting. This is the sort of book that can be read in a couple of sittings and I think would work well for bookclubs.

I look forward to checking out more books by this author.recommended83 s ???? ???? Fayez Ghazi Author 2 books4,285

- ??? ??? ?? ???? ?????? "???????" ??? ??? ?????? ?? ?? "????? ????" ???? ??????? ????? ???? ????? ???? ?? ??????? ?? "?????? ???????" ??????? ??? ???????? ?? ???????!! ?? ???? ????? ?????? ???????? ?????? ?????? ???????? ??? ??? ???? ???? ????.

- ?????? ?? ?? ?? ??????? ?????? ?????? ??????? ?????? ????? ?????? ?? ????? ?????? ??? ??? ??????? ????????? ???? ??????? ???? ????? ?????? ???? "?????" ?? ??????? ??? "?????" ?? "??????" ????? ???? ?? ????? ????? ???????? ??? ???? ?????? ??? ?????? ?????? ?????? ??????.

- ????? ?????? ??????? ?? ?????? ??? ??? ?????? ??????? ???? ??? ???? ????? ????? ???? ?????? ?????? ????? ??? ??????? ???????? ?? ???? ???????? ????? ???? ?? ????????. ??????? ??????? "????" ??????? ???????? ????? "?????" ??????? ??????? ?????? "?????". ??????? ???????? ??????? ????? ???????? "?????? ???"? ???? "?????" ?????? ?????????? ?????? ???? (??????). ??????? ?????? ???? ???????? ?????? ?? ??? ??? "?????"? ???? ?? ??? ???? ???? ?? ???????.

- ??????? ?????? ????? ???? ??? ??? "???? ????" ?? ??? ?????????? ?? ????? ???????? ???? ???? ????? ?????? "????" ????????. ?????? ??????? ??????? ??? "??????" ??? ???????? ?? ????? ???? ??????. ?????? ???? ????????? ????? ????? "?????" "????" ?? ???????? ??????? ????? ????? ?????? ??? ?????????? ?? ???? ?? ?????. ???? ????? ?????? ???? ??? ?????? "????" ???? ??????? ?????? (??? ????? ????? ????? ??????? ???). ???? ????? ?????? ??? ???????? ???????? "?????" (????? ???? ?????? ?? ????? ?????) ???? ?????? ????? "?????" ?? ?????? ??? ????? ??? ?? ??? ????? ? "????". "?????" ????? ????? ????? "?????" ?????? ??? ?????? ??????? ????? ??? "??????"? ?????? ???? ????? ?????? ??? ???????? ????? ??????? ?? ??????? ????? "?????? ???" ???? ?????? ??? ???????? ??? ?? ???? ??????? ???. ????? "?????" ??? ?????? ???????? ????? ????? ????? ????? ???? ??? ???? ??????? ?????????? ?????? ??? ????? ?????? ?????? ?????? ??????? ??????? ??????.

- ??????? ?? ????????? ?? ????????? ?? ???????? ??????? ???? ???? ?????????? ??? ????? ??????? (???????? ??????? ????)? ?? ???????? ???? ?????? ??? ???????? ?? ??? ?????? ?? ???????? ??? ???????? ??????? (????)? ?? ???????? ?????? ???????? ????????? ??????? (?????)? ?? ???????? ????? ?? ????? ??????? ????? ?????? ?????? (??????) ?? ??? ???????? (?????? ?????? ??????...). ??????? ?? ???????? ?? ????? ?????? ???????? ??? ???????? ?? ??????? ???????? ???? ???????? ?? ???????? ????????? ?? ????????????? ???? ??? ?? ?????? ??????? ?? ????? ?????? ??????? ?? ??????? ???? ????? ?????? ??????? ??? ???????. ?? ????? ?? ?????????? ?? ?????? ??? "????? ???????" ??? ?????!

- ????? ????? ??????:

????? ??????? ???? ??? ?? ?????? ?????? ????????? ?? ??????? ??????? ?? ??????? ???????? ????????? ?? ????? ??????? ????????? ?? ????? ????? ????? ???????? ????????? ?????????? ???? ??????? ?????? ????? ???????? ????????? ?? ????? ??? ??????? ???? ???????? "????" ??????? ??? ?? ????? ???? ???? ?????.

??? ????? ????? ????? ?? ?????? ???????:

1- ?????? "?????" ? "?????" ?? ?????? ?? ??? ??? ????? ?????? ???????!

2- ?????? "??? ????" ?? "?????" ??????? ??? ???? "?????" ???? "?????" ?????!!

3- ?????? "?????" (??????? ???????) ????????? ??? ?? ???? ????? (???? ????????) ????!

4- ?????? ???????? ??????? ???????? ???? ???????? ?????????? ?? ??????! ?????? ????? ?????? ?? ??? ????? ????????.

5- ???? "?????" ???? ???? ???? ???? ?????? ?? ?????? "???????" ??? "???????"!!

- ??????? ????? ?????? ?? ??? ???????? ??? "???????" ??? ???? ??????? ???????. ????? ???? ???? ?? ??????? ???????? ???????? ???? ?? ??????.

??????: ???? ??? ??????? ??? ?????? ???? ????? ???? ?????? ??????? ??????? ??????? ?????? ?????? ???? ?????.

??? ??? ?? ??????? ?? ?????? ?????? ???? ???? ??? ??? ??????:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

"?? ??? ?????? ???????? ???? ?????? ?????? ??????? ??????? ???? ??????? ????? ?? ???????? ??? ?????... ???? ?????? ??? ??????? ????? ?????? ?? ???? ?? ????? ???. ???? ??????? ???? ??? ???? ?? ???????? ??? ??? ??? ???? ?? ???????"

83 s Trish1,373 2,610

Shamsies novel was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize for 2017. It is topical: two British families with Muslim religious roots and Pakistani backgrounds cone together in a doomed pas de deux . The author Shamsie, according to cover copy, grew up in Karachi, and yet in her picture she has the round eyes of a Westerner. The cultural difficulties she writes of may not be too difficult for her to imagine, Im guessing.

I read this novel very fastit has a strange, porous density to it. The meaning of sentences are all on the surface. The detail in the opening chapter is a blind, leading nowhere except providing an excuse for a meeting of the two families. The girl's family is orphaned. The boys family needs no introduction, being daily in the news for British political leadership and therefore on display. The disconnect between the two is wide, and should be difficult to overcome. We are not entirely convinced at any time.

Lovewhat is it after alland who can lay claim to it? The just-past teenage son of a British minister? Not so fast. The beauty of the girl--is it enough when one is feted by the most desirable creatures in ones class? Not so fast. And jihadit is brought in clumsily, inauthentically, casually. It may be just those things, but I doubt it.

In the end this struck me as an early attempt by a sort-of-promising author except that there was no weight to any of it. I felt no responsibility for what the characters learned or hadnt learned, and the young peoples insistence upon their own desires was disturbing to me and un everything I have known of Southeastern Asian society.

I got no sense of the enormously consequential decision in Sophocles' Antigone , despite the epigraph quoting Seamus Heaney's translation of the play. Instead, the book could more easily be read as a reworking of Romeo & Juliet. I felt no grandeur in this novel, however. Alas.adventure america asia ...more75 s HafsaAuthor 2 books116

The fact that this book has done so well in western literary circles, eager for yet another behind the veil/AK47 escapade, is not surprising. Is it possible to have a best-selling novel that speaks to contemporary "Muslim" life, that is not about the turn to radicalism by a poorly adjusted Muslim male living in the West? It seems that the answer is no, because clearly, this kind of narrative is the only one the Western readership is craving for.

This novel attempts to "humanize" Western Muslims, but does so in a way that once again falls into the same, old tropes. The writing was poor, the characters uninspiring, and fixed in their archetypes. Parvaiz's journey to Syria/Turkey was so stereotypically rendered, and felt they were taken from a counter-terror manual on "what to look out for." I could not believe the sections on the hijabi and her sexual escapades with her self-hating pseudo-Muslim lover--it read the poorly imagined fantasies of an orientalist. In an attempt to perhaps complicate Muslim women or given them agency, they become further sexualized and yet only from the perspective of the males in the story. The parts about sex and desire felt forced, awkward, almost in a "hey muslims (want to) do it too" kind of way.

I long for the day when stories with Muslim characters, or even stories that speak to contemporary Muslim life, are written in a way that is not subservient to the western gaze.literature72 s Paul FulcherAuthor 2 books1,453

Deservedly the winner of the 2018 Women's Prize for Fiction:

What do you say to your father when he makes a speech that? Do you say, Dad, youre making it OK to stigmatise people for the way they dress? Do you say, what kind of idiot stands in front of a group of teenagers and tells them to conform? Do you say, why didnt you mention that among the things this country will let you achieve if youre Muslim is torture, rendition, detention without trial, airport interrogations, spies in your mosques, teachers reporting your children to the authorities for wanting a world without British injustice?

[...]

If youre nineteen and female youll get some version of a hard time for whatever you wear. Mostly its the kind of thing thats easy to shrug off. Sometimes things happen that make people more hostile. Terrorist attacks involving European victims. Home Secretaries talking about people setting themselves apart in the way they dress. That kind of thing.

Aneeka (Antigone) to Eamonn (Haemon)

Were in no position to let the state question our loyalties. Dont you understand that?

Isma (Ismene) to Aneeka (Antigone)

Khamila Shamsies Home Fire is a 21st Century rewrite of Sophocless Antigone. It perhaps wasnt the best book on the 2017 Man Booker longlist, if measured by pure literary merit, it was the most important and thought provoking.

Studying Antigone in preparation for Home Fire I was struck, as I imagine Shamsie was, by the contemporary relevance of three key Greek concepts, left untranslated in the version I read.

1) the ambiguous use of the word nomos - which to Antigone denotes customs and values, but to King Creon the laws of the land (https://www.britannica.com/topic/nomo...)

2) Antigone's prioritisation of philia (obligations to friends, family: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philia) over obligations to the state, and Creon's explicit rejection of that stance, (Whoever deems a philos more important than a fatherland, this man I say is nowhere.) or, as in Seamus Heaney's rewrite of the play, which forms the epigraph for Home Fire:

The ones we love . . . are enemies of the state.

3) and most strikingly in a 2016-7 context Antigone's lament that she is a "metic, not among the living nor among the dead" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metic). In modern day parlance, she is essentially proclaiming herself a citizen of nowhere, to use the accusatory phrase used in 2016 by the newly appointed British Prime Minister towards those who would calls themselves citizens of the world.

Shamsie relocates Antigone to Britain in the 2nd half of the 2010s, and her conflict is not just between family and state, but between ones religious and cultural beliefs, particularly for British Muslims, and both family and state. And she also addresses the troubling question of why young people are, despite the well documented excesses of the regime, attracted to leave their country of residence and their families and journey to Islamic State,

In her retelling Creon becomes Karamat Lone, newly appointed British Home Secretary (one of the four great offices of state) and with his sights on even higher office:

The accompanying article described the newly elevated minister as a man from a Muslim background, which is what they always said about him, as though Muslimness was something he had boldly stridden away from. Inevitably, the sentence went on to use the phrase strong on security.

In the real world. 2017 Britain is a country where, on the one hand, London has (since the first draft of Home Fire was written) elected an openly Muslim mayor despite a dog whistle campaign by his opponent to try to link him to Islam extremism, but on the other hand, where someone running to be a new Member of Parliament in 2010 and now a senior Cabinet minister - felt obliged to announce at the hustings: My own familys heritage is Muslim. Myself and my four brothers were brought up to believe in God, but I do not practise any religion. My wife is a practising Christian and the only religion practised in my house is Christianity. I think we should recognise that Christianity is the religion of our country.And also where, in 2014, the then Home Secretary now in 2017 the Prime Minister of the Citizens of Nowhere speech introduced powers to strip dual citizens suspected of involvement in terrorism of their British nationality. In the novel, Kamarat Lone, goes further:

The day I assumed office I revoked the citizenship of all dual nationals who have left Britain to join our enemies. My predecessor only used these powers selectively which, as I have said repeatedly, was a mistake.

Home Fire - as with Preti Taneja's recent wonderful retelling of King Lear, We That Are Young - is told in five sections, in the third person from the perspectives of the key characters:

- Isma (Ismene), a young woman and LSE trained sociologist

- Eamonn (Haemon), son of the Home Secretary

- Parvaiz (Polyneices), Isma's 19 year-old younger brother

- Aneeka (Antigone), Parvaiz's twin sister, studying law at LSE, and

- Karamat (Creon), whose Irish wife Terri fills the role of the prophet Teiresias

The novel opens with Isma at Heathrow undergoing an interview from British immigration authorities, although she is actually leaving the country to start a PhD in America. In the 21st Century security state any Muslim leaving the country, particularly with Isma's family background (see below) is potentially open to suspicion as to whether their ultimate route might be Islamic State: indeed, unknown to anyone but his very close family, Ismas brother, Parvaiz, has done precisely that.

Do you consider yourself British? the man said.

I am British.

But do you consider yourself British?

Ive lived here all my life. She meant that there was no other country of which she could feel herself a part, but the words came out sounding evasive.

The interrogation continued for nearly two hours. He wanted to know her thoughts on Shias, homosexuals, the Queen, democracy, The Great British Bake Off, the invasion of Iraq, Israel, suicide bombers, dating websites. After that early slip regarding her Britishness, she settled into the manner that shed practiced with Aneeka playing the role of the interrogating officer, Isma responding to her sister as though she were a customer of dubious political opinions whose business Isma didnt want to lose by voicing strenuously opposing views, but to whom she didnt see the need to lie either. (When people talk about the enmity between Shias and Sunni, it usually centers around some political imbalance of power, such as in Iraq or Syriaas a Brit, I dont distinguish between one Muslim and another. Occupying other peoples territory generally causes more problems than it solvesthis served for both Iraq and Israel. Killing civilians is sinful¬thats equally true if the manner of killing is a suicide bombing or aerial bombardments or drone strikes.)

There were long intervals of silence between each answer and the next question as the man clicked keys on her laptop, examining her browser history. He knew that she was interested in the marital status of an actor from a popular TV series; that wearing a hijab didnt stop her from buying expensive products to tame her frizzy hair; that she had searched for how to make small talk with Americans.

The dangers of Googling while Muslim feature frequently in the novel, fears which Shamsie admits dogged her when researching the novel.I was very aware of Googling while Muslim while writing this book. When I started to research, I would do stupid things, look at three relevant websites, then go look at some really trashy celebrity stuff for a while. There was a part of my brain that was saying, what will I say if intelligence agencies come to my door and want to know why Im looking up this stuff?Most strikingly, from the same interview:Q: Would you have published Home Fire before you had the security of knowing you were a British citizen?

A: No, absolutely not.http://www.vogue.com/article/kamila-s...

In America, Isma suddenly encounters a handsome youth, in a rather Mills and Boonesque moment.

By mid-afternoon the temperature had passed the 50° F mark, which sounded, and felt, far warmer than 11° C, and a bout of spring madness had largely emptied out the café basement. Isma tilted her post-lunch mug of coffee towards herself, touched the tip of her finger to the liquid, considered how much of a faux pas it might be to ask to have it microwaved. She had just decided she would risk the opprobrium when the door opened and the scent of cigarettes curled in from the smoking area outside, followed by a young man of startling looks.

She soon recognises him as Karamat Lone's son:

Eamonn, that was his name. How theyd laughed in Wembley when the newspaper article accompanying the family picture revealed this detail, an Irish spelling to disguise a Muslim name Ayman became Eamonn so that people would know the father had integrated. (His IrishAmerican wife was seen as another indicator of this integrationist posing rather than an explanation for the sons name.)

There is history between the two families. Isme, Aneeka and Parvaiz's father Adil Pasha had been a jihadi himself: their last contact with him a phone call from Afghanistan in late 2001. In 2004 they found out, from a fellow prisoner, now released that their father had been captured in early 2002, imprisoned and tortured in the Bagram Theater Internment Facility and then died on route to Guantanamo. A friend of the family contacted a cousin, now the local MP - one Karamat Lone, then at the start of his political career - for help in finding where his body might be, but he refused

They're better off without him

One issue Shamsie faced in re-writing Antigone was how to incorporate the incest/father murder of Oedipus, Polyneices and his sister's father: changing this so that father and son are both jihadis, was a very neat solution, and does away with the fourth sibling Eteocles (killed by Polyneices in the play) as Parvaiz's unpardonable sin, rendering him a non-person in Karamat's eyes, is joining Islamic State.

The destiny of sons's to follow their father is a key theme of the novel, albeit one that I struggleda little with as so manifest in a 21st Century context. As Eamonn tries to explain to one of the sisters:

For girls, becoming women was inevitability; for boys, becoming men was ambition. He must have seen her look of incomprehension because he tried again. We want to be them; we want to be better than them. We want to be the only people in the world who are allowed to be better than them.

And incomprehension cuts both ways: Eamonn tries, and fails, to understand how it might feel to be Parvaiz or his sisters:

He tried to imagine growing up knowing your father to be a fanatic, his death a mystery open to terrible speculation, but the attempt was defeated by his simple inability to know how such a man as Adil Pasha could have existed in Britain to begin with.

I won't spoil what happens in the rest of the novel. Shamsie is to be credited for managing to:

- adhere faithfully to the original - even incorporating nods to signature elements such as the dust storm that appears at one crucial moment, yet

- maintain narrative tension - it is typically only afterwards that one recognises how the action follows the play, and

- update the play's themes for a 21st Century setting - for example the role of Coryphaeus and the chorus is taken by the press - and highly topical issues.

The novel has some powerful things to say about dual nationality and identity - and the approach of allowing each character their perspective provides a relatively balanced view, albeit it is clear that Shamsie's sympathy's are not with Karamat Lone's approach to stripping those joining Islamic State of their citizenship and their right to return, even for burial when dead, to the UK.

She also, through Parvaiz, provides insight into what draws young people to Islamic State, drawing on the interviews in Gillian Slovo's verbatim play Another World: Losing our Children to Islamic State. She describes a recruitment video for Islamic State - note the dissonant images of violence interspersed with the idyllic scenes:

Men fishing together against the backdrop of a beautiful sunrise; children on swings in a playground; a man riding through a city on the back of a beautiful stallion, carts of fresh vegetables lining the street; an elderly but powerful-looking man beneath a canopy of green grapes, reaching up to pluck a bunch; young men of different ethnicities sitting together on a carpet laid out in a field; standing men pointing their guns at the heads of kneeling men; an aerial night-time view of a street thrumming with life, car headlights and electric lights blazing; men and boys in a large swimming pool; boys and girls queuing up outside a bouncy castle at an amusement park; a blood donation clinic; smiling men sweeping an already clean street; a bird sanctuary; the bloodied corpse of a child.

or as Parvaiz puts it rather more simply when he arrives in Raqqa:

Despite his disquiet at the spiked heads and veiled women, the blue skies and the camaraderie of the men slumped in beanbags promised the better world hed come in search of.

And the book also doesn't spare those who make life more difficult for their fellows by their own actions. As a Pakistani relative of Aneeka tells her when she arrives in the country as the novel reaches its dramatic climax:

Did you or your bhenchod brother stop to think about those of us with passports that look toilet paper to the rest of the world, who spend our whole lives being so careful we dont give anyone a reason to reject our visa applications. Dont stand next to this guy, dont follow that guy on Twitter, dont download that Noam Chomsky book. And then first your brother uses us as a cover to join some psycho killers, and then your government thinks this country can be a dumping ground for its unwanted corpses and your family just expects us to jump up and organise a funeral for this weeks face of terrorism.

And now youve come along, Miss Hojabi Knickers, and I have to pull strings I dont want to pull to get you out of the airport without the whole worlds press seeing you, and it turns out youre here to try some stunt, I dont even know what, but my family will have nothing to do with it, nothing to do with you.

I said at the review's start that this wasn't perhaps the best book on the Booker shortlist measured by literary merit alone. As per the example quote above, the Isme section has tinges of a Mills and Boon romance and that focusing on Parvaiz elements of a cheap Clive Cussler thriller (per Gumbles Yard's excellent review https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...).

However the writing becomes more powerful in the latter two sections, as it move on to both the highly personal and yet public anguish of Aneeka, interspersed with excerpts from tabloid newspapers (who rename Aneeka 'Knickers' and Parvaiz 'Pervy' as they seize with glee on the sex scandals in the story) and then the political machinations of the Home Secretary. And it struck me that the style choices in the first sections may have been that: choices, with Shamsie using the character's own worldviews to colour her third-person narration.

Overall - a novel I would be happy to see win the Booker, albeit there are many other strong books on the exceptional 2017 list: Autumn, Reservoir 13 (my personal favourite), Solar Bones, Exit West and Lincoln in the Bardo would form the rest of my personal shortlist.2017 booker-201772 s Roman Clodia2,581 3,392

Delighted that this has now been recognised as the magnificent book it is: well done Women's Prize panel!

Inspired by Sophocles' Antigone, this has a slightly shaky start but then soars into an outstanding tragedy of love, politics, justice and humanity. By drawing on Athenian tragedy, Shamsie makes the point that clashes of civic law vs a deeper, more humane sense of what is right have always been contested, and the tension between family and state always problematic. What she does so brilliantly in this book is to take these questions and give them an acutely charged contemporary relevance that leaves the reader shaken.

I have been lucky enough to read an ARC (thanks Bloomsbury and NetGalley!) so can't say too much so far in advance of publication, but this is a book which takes complicated public issues and makes them intimate and personal. Refusing to simplify or neaten, Shamsie has produced a book which treats matters both horrific and beautiful with clear-sightedness, intellectual grace and compassion.

A searing, towering, magnificent piece of storytelling which deserves to win prizes and be read by everyone - brava, Ms Shamsie!65 s ????? ??????Author 23 books27.1k

???? ????? ???? ?? ???????? ???? ?????? ?? "?????" ??? "?????"? ??? ????????? (???????? ??????) ?????? ?????? ??? ?? ????? ?????? ?????? ??? ?????. ????? ????? "??????" ????? ??? "?????? ???????"? ??????? ????? ?????? ??????? ?? ?? ????? ???.

????? ??????? ??? ????? ??????? ??? ????? ??????????????? ????? ????????? ??????? ?????? ???????? ???????? ???? ????? ????? ????????. ??? ??????? ?? ???? ?????? ??? ?????? ??? ????? ??????? ????? ???????? ???? ????? ???????.

???? ??? ?????. ??????? ???? ????? ????????? "???????" ??? ???? ??? ???? ???? ??? ???? .. ??? ??????? ???????.

??????? ?????? (????? ?????? ???????)? ?????? ???? ?????? ??????.

???? ??? ??????? ??? ????? "?? ????"

66 s Reading_ Tamishly4,802 2,952

*I don't this one at all.

Not worth the hype. Worst read of 2019.

Please do not get fooled by the first 2 chapters.

After those few pages, the story becomes too dragging and monotonous.

The supposedly main character who was introduced in the first 2 chapters gets totally neglected and has almost no part in the plot, which is 'What the hell is going on?' till the last page of the book!

It started out good. Yet the rest (7 out of 9 chapters) were part of a badly written young adult fiction, part trying to focus on the life of those people directly affected by terrorism/being Muslims/being a muslim in another country but most part of the book was so lost and unfocussed that I totally lost interest after the 4th chapter.

The 3rd chapter was so disgusting. This is the first abrupt warning that the book was going nowhere!

The character built up and the narration were good so far...until I started reading the third chapter.

So many issues regarding the racism and discrimination happening in the lives of the people mentioned but none of it were not really affecting their lives it seemed from the way the characters were behaving. I really couldn't find myself connected to the rest of the characters till the end. For a story that would have made the readers feel strongly about the issues and the lives of the people belonging to the Muslim community and the ; for what drives many youngsters and men into many circumstances and all which the author tried to describe yet I cannot relate as much as I wanted to. I really tried my best to understand and feel..but even the last lines where I was supposed to be crying and not wanting to finish up the story didn't make much difference.

There was no chemistry amongst the characters; as much as there was so much potential to portray all kinds of emotions...yet the lines and the sequence in which the story was written made everything fall so flat.

In short,the ending part or the plot has nothing much to offer.

Autor del comentario:

=================================