oleebook.com

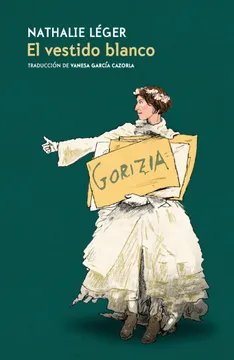

El vestido blanco de Nathalie Léger

de Nathalie Léger - Género: Cronica

Sinopsis

En marzo de 2008, la artista italiana Pippa Bacca emprende una performance tan atrevida como llena de buenas viajar en autostop de Milán a Jerusalén vestida de novia, en una suerte de peregrinación antibelicista por países en los que aún es palpable el rastro de la guerra, como una forma de reivindicación de la paz y el amor universal, representados por el vestido blanco. Una década más tarde, la autora francesa Nathalie Léger, sobrecogida ante la historia de Bacca y su fatal desenlace, decide indagar en los motivos que llevaron a la joven a emprender un viaje tan peligroso.

Mientras avanza en su investigación, Léger visita unos días a su propia madre y descubre el anhelo urgente que esta siente de revelarle el trato humillante e injusto que hubo de padecer durante el proceso de divorcio de su padre en los años setenta, y le pide que dé voz a esta verdad.

Apoyándose en el simbolismo del vestido blanco como punto de partida y con la precisión y clarividencia a la que nos tiene acostumbrados, Nathalie Léger vincula dos historias de mujeres que en apariencia no guardan ninguna relación y, con un estilo bello, sutil y reflexivo, pone de manifiesto la importancia que tiene tanto en el ámbito familiar como en el arte la búsqueda de un relato que nos haga justicia.

Descargar

Descargar El vestido blanco ePub GratisLibros Recomendados - Relacionados

Reseñas Varias sobre este libro

The first page of La robe blanche contains a total of 27 commas plus 3 semi-colons in only 6 sentences.

4 of the sentences describe a tapestry of an allegorical scene featuring a torn white dress, so the reader knows by the end of that first page that Nathalie Léger is adept at connections (aren't commas the stitches of a sentence), as well as at creating metaphors. And the reader will soon find out that the torn white dress is central to the meaning of the entire book, and that both the notion 'torn' ('déchiré', in French, which carries an entire tapestry of allusion in its 7 heart-rending letters) and the notion 'white dress' (of which there are 4 in this book), will connect as neatly as commas do the separate sections of the narrative to make a complete ensemble.

*

I read this as an ebook, and because it's so easy to highlight the passages we in an ebook, I highlighted so many individual sections that they began to connect with each other to make one nonstop highlight.

*

I've been thinking about dialogue in novels lately because of a couple of references by goodreads friends to how dialogue can sound artificial in fiction, so I paid attention to how Nathalie Léger handled dialogue, or rather I didn't pay attention to it because I didn't register for a while that she was actually using dialogue, so seamlessly does it merge into the narrativewhich happens mostly inside the mind of the narrator but much of which concerns a prolonged conversation with her mother, whose words are heard very naturally inside the narrator's account. A skillful technique.

*

The narrator uses words carefully, and she meditates on them frequently, cliché phrases for example, which she uses and then turns inside out, just as she turns the notion of the white dress inside out, especially the clichéd 'white wedding dress'. She particularly s long trains of words, sewn together neatly with commas so that they make for easy reading. Certain individual words recur, 'la bonté' (goodness) for example, and while the narrator is meditating on that word, the word 'tuer' (to kill) is overheard, and the more we read on, the more the book is rhythmed by those two words, and both link with 'déchiré' (torn) which occurs at the beginning and at the end of the book.

*

When I slotted this book in between two Luís Sagasti books, I had no idea how well it would rhyme with both. Sagasti's books are collage-type accumulations of fact and fiction around a central theme. His facts are taken from nature, from music, and from performance art, and his fictions are inspired by the same. Nathalie Léger composes with fact and fiction too, but instead of accumulating diverse material, she concentrates on two main happenings, one, a performance art piece, and the other an episode in her narrator's personal life, but both centred on white dresses stitched from panels of material, and on the torn-apart destinies of those who wore them. Ah, there's the 'déchirant' idea again. Truly heart rendingand I know that's a cliché description but it suits.memorable-21st-century-books read-in-french68 s Paul FulcherAuthor 2 books1,528

Elle voulait porter la paix dans les pays qui avaient connu la guerre. Elle pensait, disait-elle, faire régner lharmonie par sa seule présence en robe de mariée. Ce nest pas la grâce ou la bêtise de son intention qui ma intéressée, cest quelle ait voulu, par son geste, réparer quelque chose de démesuré et quelle ny soit pas arrivée. Une robe blanche suffit-elle à racheter les souffrances du monde? Sans doute pas plus que les mots ne peuvent rendre justice à une mère en larmes.

She wanted to bring peace to countries that had known war. She said she thought she could do that simply by wearing a wedding dress. I wasn't interested in the grace or foolishness of her intentions; what interested me was that she hoped this gesture would be enough to mend something that was so out of proportion with it - and that she did not make it. Can a white dress ever be enough to make amends for the world's torments? Probably no more than words can ever be enough to do justice to a weeping mother.

La Robe Blanche by Nathalie Léger has been translated by Natasha Lehrer as The White Dress, and edited and published by Cecile Menon of the wonderful publisher Les Fugitives. It forms part of a trilogy of related works with:

'L'exposition' (2008), translated by Amanda DeMarco as 'Exposition' (Les Fugitives 2019):

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...?

'Supplément à la vie de Barbara Loden' (2012), translated by Natasha Lehrer & Cécile Menon as Suite for Barbara Loden (Les Fugitives 2015):

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

'La Robe Blanche' (2018), translated by Natasha Lehrer as 'The White Dress' (Les Fugitives 2020)

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

As with the first two books, this is an experimental novel in the form of a mixture of auto-fiction, biography and art essay.

The White Dress is inspired by the real-life story of Italian performance artist Pippa Bacca (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pippa_B... and https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/19/th...).

She and fellow artist Silvia Morro departed from Milan on 8 March 2008, wearing wedding dresses, in an artistic performance and peace mission they called "Brides on Tour". As explained by the foundation that supported them they planned on (google translation of the original Italian): hitchhiking through the Mediterranean countries devastated by recent wars, with the aim of bringing them a message of peace, hope and solidarity, through the journey itself and a series of rituals / performances of great symbolic value.

En route, Pippa Bacca stopped to wash the feet of midwifes at each stop:

Silvia Morro later explained (interview at https://web.archive.org/web/201203060... google translation)

Pippa identified as a key point of her artistic research a highly symbolic gesture: washing the feet of midwives to honour the oldest profession in the world, which makes birth possible.

By recording their voices, she invited them to explain what birth, the life to which they themselves contributed every day with their profession, meant to them. A meeting and a peaceful confrontation that almost always also brought out their fears, their joys and their feelings at the moment when they became mothers in turn.

Sometimes midwives were contacted directly by Pippa, other times by the same families who were hosting us.

Before meeting Pippa some of them were perplexed, almost suspicious, because they did not understand the meaning of washing their feet. As if by magic, however, when they arrived in front of Pippa it was as if something was taking in them: I saw them sit in total confidence, entrust their feet to the hands of my partner, answer the questions, get excited, sometimes giving her some completely surprising answers

The two had aimed to reach Israel, and end their journey by ceremonially washing the wedding dresses, but having travelled through Slovenia, Bosnia, Bulgaria and Serbia, their journey ended in Turkey, where Pippa was abducted by one driver, raped and murdered. One of her rules for the journey was that she wouldnt refuse an offer of a lift; she told a journalist en route its a way of showing trust to your fellow human beings. To prove that when you show trust you receive nothing but goodness.

The novel opens with an image of a tapestry hanging in the author/narrators family home, itself inspired by the 2nd panel of Boticellis Nastagio degli Onesti, an image that combines both the vision of a women in a white dress being pursued and killed, but also reminds the narrator of the undercurrents of menace in her family home.

As the novel tells us, when Pippa Baccas murder was announced, the tall, crazy poet Alda Merini who called herself the poet of shame wrote:

(as translated by the author into French):

Robe blanche

pour aller épouser ta mort

qui est aussi la nôtre.

Tu tes vêtue de blanc

Et puisque ton âme mécoute

Je voudrais te dire que la mort

Na pas le visage de la violence

Mais quelle est le soupir dune mère

Qui viendrait te chercher au berceau

Dune main légère.

Je ne sais que te dire

Moi je ne crois pas

A la bonté des gens

Jai déjà vécu tant de douleurs

Mais cest comme si je voyais mon âme

Vêtue pour les noces

Qui séchappe du monde pour ne pas crier.

(as translated by the translator into English) :

White dress

to go forth and wed your death

which is also ours.

You wore white

and because your soul is listening to me

I wanted to tell you that death

does not have a violent face

it is the sigh of a mother

who has come to pick you up from your cradle

with a light hand.

I don't know what to tell you

I dont believe

In the goodness of people

I have already experienced so much pain

But it's as though I see my own soul

dressed for the wedding

escaping the world in order not to shout

The text intertwines two competing claims on the narrators intention.

- Her research into Baccas ultimately doomed project and her attempts to understand its mixture of the profound and the naïve, simultaneously significant and trivial in her gesture;

- Her relationship with her mother, who want the narrator to help her achieve retrospective justice against her estranger husband, the narrators father, by telling her story. Despite him being the adulterer in the relationship, he successfully and humiliatingly sued her for divorce, and gained custody, on the grounds of her inadequacies as a wife (the court apparently finding thatthe wifes multiple shortcomings regarding her obligations arising from the marriage that were of a kind that explains and even excuses adultery)

Léger draws on historical performance artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Marina Abramovic and Marie-Ange Guilleminot, the oral testimonies of Svetlana Alexievich (a key inspiration for her mother, who tell's her, towards the novel's end that, those in Alexievich's books, youve given me back my living voice) and, in the following passage, which feels key to the link between the twin themes, the novels and poems of Balzac, Conrad, Claudel, Mallarme, Joyce and WG Sebald:

A single word stands out and falls: 'crushing'. It has no prosodic beauty, but it immediately evokes what I am after. The word holds within in all the tears, but without drowning in them, it's not sentimental, it stands beyond the rapacious shrine of existence, beyond generalisation, and it holds in its perpertual grammatical present my mother's loneliness, that of Blanche de Mortsauf, Lord Jim's silence, Prouhèze parting from Rodrigue, the day Gretta learns of the death of Michael Furey, the broken words of Mallarmé grieving the death of his son, Jacques Austerlitz's reunion with his past (Jacquot, Jacquot, is it really you?), the naïve impulse of this young women in her white dress. 'Something profoundly shocking or upsetting that affects greviously,' according to the dictionary. Something - aside from moralistic preaching or a roll of the dice - that calls for reflection.

A review that does the book more justice than I can:

https://theartsdesk.com/books/nathali...

An interview with the author: https://bombmagazine.org/articles/nat...

A moving and powerful piece and when considered together with its companion novels, a masterpiece. 5 stars, awarded for the trilogy as a whole.2020 les-fugitives sub-les-fugitives-2020-333 s Alwynne734 975

With The White Dress Nathalie Leger concludes a loose trilogy mixing the autobiographical and imagined with the academic and analytical. Each is an unorthodox examination of a different woman, all of them involved in creative work relating to the performed and the visible. But these studies, falling between fiction, biography and personal confession, also feature elements of an ongoing dialogue between Leger and her mother. One that suggests deep-rooted conflict and ambivalence, with Leger constantly moving from repulsion and frustration to affection and back again. In this final piece what, at times, seemed an unfathomable, tangential combination of Legers thoughts on her chosen subjects and repeated, interjected conversations with her mother finally forms a coherent whole. And I found the result ultimately more intimate, more personal, and more immediately compelling than either of the books leading up to it. Legers ostensible topics performance artist Pippa Bacca, whose lifes come to be defined by her brutal death. In 2008, Bacca set out with another artist to perform an act of peace, which, from Legers description, seemed part reconciliation, part expiation. Dressed in flowing, white, wedding gowns, the women planned to hitch-hike from Milan to Jerusalem: visiting sites associated with loss and war; breaking away to spend time with those, midwives, they linked to lifes more fertile possibilities. Their only firm rule, never to turn down a lift when offered. But after briefly separating, Bacca accepted a solo ride from a man who then raped and murdered her.

However, Leger doesnt open with Bacca but a seemingly abstract reference to another slaughtered woman, spinning off into a series of musings on her thwarted attempts to write about Baccas performance. At first, I was confused by Legers fragmented, meandering narrative, it seemed blurry and off-centre. The only thing that seemed clear was that Legers interest in her subject stemmed from an inability to understand Baccas goal to Leger absurd, perhaps horribly naïve, in the underlying emphasis on the possibility of goodness. As Leger discusses Bacca with the people around her, its striking how many of them frame Baccas performance piece in severely judgemental language: friends of Legers mother suggest Bacca was asking for it, critics and commentators remark on her foolishness, the ridiculousness of her wedding outfit. Their reactions posed questions which cast a shadow over Legers pages forcing me to interrogate my own response to Baccas actions, and raising important issues around art and gender, and the harsh angles from which women are too often viewed. And I found myself thinking about Legers earlier studies, her numerous references to iconic women Monroe, also remembered as much for how they died as how they lived. The contrast between La Castiglione in Exposition and Bacca: one attempting to rigidly control her image, the other to make herself vulnerable, to offer up the possibility of productive connection. Yet both ended up subjected to similar kinds of relentless, savage scrutiny: for Bacca the spotlight continually trained on her and not the man who killed her. At first it looked as if Leger might become enmeshed in constructing an equally negative story in which Baccas both victim and, somehow, perpetrator of her own murder - just as Legers mother's portrayed as a martyr- figure, blighting her own life with her refusal to move beyond a long-ago, painful divorce. But slowly and unexpectedly, it became clear that Legers writing about two white dresses and two women - Bacca and Leger's mother - who put them on with the hope of a better future. But instead, both women became bound up with the sacrificial, and both were derailed, albeit in different ways, and through different, yet inextricably linked forms of violence.history-culture-politics-art memorable-2021 read-women-wit-challenge-2021 ...more33 s Hugh1,274 49

This was my first experience of Léger, though her name has been familiar since her previous Les Fugitives book Suite for Barbara Loden was championed by Paul Fulcher a couple of years ago. I found it an intriguing and enjoyable read, but not as easy as its length would suggest because much of it is written in long paragraphs and fairly long sentences.

The theme that gives the book its title is the Italian performance artist Pippa Bacca, who attempted to hitchhike from Italy to Jerusalem wearing a wedding dress, but was murdered soon after reaching Turkey. The author's attempts to get beyond the bare bones of this story are largely frustrated, and much more of the book is about the author's relationship with her mother and the traumatic circumstances in which her father divorced her. A number of other performance art pieces are also described, making parts of the book a little reminiscent of A Line Made by Walking. The whole thing works rather well, and had it been a little longer I might have given it a 5-star rating.modern-lit read-2021 translations25 s Dave SchaafsmaAuthor 6 books31.8k

I went to Staten Island.

To buy myself a mandolin

And i saw the long white dress of love

On a storefront mannequin

Big boat chuggin' back with a belly full of cars. . .

All for something lacy

Some girl's going to see that dress

And crave that day crazy--Joni Mitchell, Song for Sharon

The White Dress appears to be the third in a triptych by Nathalie Leger, one short book each about a different woman and her impact on the world. I have read in the past two weeks two veritable gut punches of books; the first, a brutal anti-war book, Dalton Trumbos Johnny Got His Gun, and this book, an equally brutal book about war, though very different, with lyrical passages, about the death in 2008 of a performance artist (this cant be a spoiler, exactly, as the events were known worldwide and are revealed on the books back cover clearly), Pippa Bacca, who wore a white wedding dress hitchhiking to various war-torn countries in a series of acts designed to promote peace. She performed designed activities in each town she visited, such as washing the feet of midwives in one town. Shed also conform, as performance artists do, to a series of preset rules; one of hers got her killed, that she would never refuse any ride from anyone, in an act of trust.

She said, "I'm tired of the war

I want the kind of work I had before

With a wedding dress or something white

To wear upon my swollen appetite"--Leonard Cohen, Joan of Arc

In this book Leger writes an essay about Bacca, struggling to understand her act of sacrifice. As with The Cellist of Sarajevo, who risked his life playing in a dangerous public square in honor of people he knew who had been killed there, Bacca was seen by many as foolish, living her art far too dangerously. Many failed to understand her purpose--whats the point of getting killed in a war to protest war!!??--and even Leger at one point calls her naive, though she is ultimately sympathetic. Legers ultimate goal, however, is to support artistic acts, feminist art, pacifist acts, even if they are not successful in stemming the tide of violent history. Theyre a kind of light against the darkness, acts-- the wedding dress itself--of hope, and love. Haters gonna hate, as Taylor Swift sings. But you do what you have to do to take a stand against hate, nevertheless.

Digressive, wandering between her research on Bacca and other women performance artists and the purpose of art, Leger writes of Bacca, but she is challenged at the same time as she writes by her mother, who suffered all of her life by being abandoned by her husband and dragged through divorce courts by her (philandering) husband as having caused his affair. The point for Leger is to tack back and forth between these two stories, two women who live in precarity, who live at risk of being eliminated or abused or ignored. In both cases other women sometimes do not support these women Leger finds ultimately admirable, and are even critical of them.

Bacca dies at the hands of a man who picks her up on a road near Istanbul, but in her documentation Bacca makes it clear that in her hitchhiking many kind and generous and humane men had picked her up and supported her work, on her travels over months. One man was of course monstrous and seems in a way to cancel out all the rest, to make you shake your fists, to scream, to cry, to possible believe that humans are unreclaimable, irreducibly cruel, even evil. But many good people understood her work and supported it as she traveled.

Bacca writes of other performance artists--a woman who pushes a block of ice across a public square, a woman who sits in a chair and recites a banal text about waiting.

Svetlana Alexievich writes a book of testimonies of women, not a history of war but of feelings. . . Someone needs to write a book about war that manages to make the reader feel such deep nausea that the very idea of war becomes abhorrent. But Leger's book is as much about men--violent, callous, arrogant men--as much as it is about war, but maybe it all comes to the same thing.

Many women artists feature wedding dresses, as it turns out, so symbolic an object that it is, so fraught with complexity for Leger, as for many women. Serbian artist Marina Abramovic put on a white dress and sat for four days on a huge mound of animal bones to protest war, the stench of rotting flesh permeating the air as she washed the bones with a brush, wiping the blood off her dress.

Legers actual description of the murder of Pippa Bacca--aspects of the events surrounding it documented by the murderer with her own video camera--is so devastating it painfully took my breath away, as have so many things, Ill say in the past several years, but I was so caught by surprise that I was almost paralyzed, speechless. I think art may not do as much as we want it to save the world, but that doesnt make it useless or meaningless. Leger stands for artists, for art, for women, against war, against violence, against the abuse of power, and cruelty and hate. Can I call Legers book or Baccas art useless because this man also exists?

art books-loved-2022 feminism ...more21 s Uro ?urkovi?714 174

Sve vie mi ide na ivce predstavljanje Balkana kao karikature-koja-to-nije, crne rupe Evrope, mra?nog budaka koji je divalj, bolestan, ali i zanimljiv. Nije to skorija moda, ve? fenomen dugog trajanja dovoljno je setiti se Bugara iz Volterovog Kandida da bi se ovo ?inilo neiskorenjivim. Bilo kako bilo, ovaj roman je jo jedan primer pseudosubverzivnog, odbojno intelektualizuju?eg ostvarenja koje vapi da bude snano, a ne uspeva. U njemu ima mesta ne samo za razli?ite ob ?amotinje savremenih umetnika od instalacija od telesnih izlu?evina, do jadno povrnih i neoriginalnih politizovanih ?itanja stvaralatva Svetlane Aleksijevi? i Marine Abramovi?, ve? i sumanuta izmiljotina da na Balkanu postoji obi?aj da se muu dodeljuje metak na dan ven?anja da moe da ubije enu ukoliko proceni da mu je neverna i to se naziva honeymoon cartridge?!? Opisano primerima savremene srpske knjievnosti, ovo je kao vetije napisana verzija Slobode govora Vladana Matijevi?a, ili feministi?ka razrada odabranih stranica Timinog Quattro Stagioni-ja. Da se razumemo, nije ovde sve omaeno, ali je neto za ta sam siguran da se, uprkos o?iglednoj velikoj ambiciji autorke i sasvim korektnog stila, zaboravlja brzo nakon ?itanja. Ipak, ne treba smetnuti sa uma uasnu sudbinu Pipe Bake (Pipa Bacca), koja je, uz pri?u o autorki i njenoj majki, u sri ovog dela. Ova italijanska umetnica je htela da do?e autostopom do Izraela u ven?anici ?ime bi promovisala toleranciju, mir u svetu i zajednitvo u dobru. Njena namera je bila da putovanje bude jedinstven performans koji bi pokazao mo? poverenja i povezanosti me?u ljudima. Poduhvat je prekinut na najgori mogu?i na?in Pipa Baka je silovana i zadavljena tokom putovanja kroz Tursku. I to je sve toliko uasno da teko da moe ita vie da se kae.19 s Carlos170 89

Au Japon, où l'on parle la langue la plus compliquée que j'ai rencontrée dans ma vie et celle que j'ai essayé à un moment donné d'apprendre pendant mon séjour dans ce merveilleux pays (échouant héroïquement, presque comme un samouraï mal habillé, un Mifune de troisième ordre...), un seul mot définit le cur, l'âme et l'esprit : kokoro. Et cela pourrait être traduit littéralement par ressentir la pensée ou son contraire, penser le sentiment. Oui, je sais, traduire comme ça conduit à des résultats inattendus et peut-être même bizarres, du moins pour notre logique occidentale. Combien il y a à apprendre des autres cultures.

Mais, loin de ces enjeux plutôt linguistiques, culturels et même de style, kokoro est le terme qui pourrait parfaitement décrire l'écriture de Nathalie Léger, où raison et cur se confondent et fusionnent formant un tout indissociable. La complexité de ses histoires, dit-elle, est le fruit d'une jubilation d'écriture. A mon avis, la lecture de son uvre devient aussi une révélation, qui ligne après ligne se nourrit de petits détails qui finissent par devenir dénormes découvertes.

Ayant une connaissance approfondie du travail de Roland Barthes et surtout Samuel Beckett (Les Vies Silencieuses De Samuel Beckett), l'auteure est sans aucun doute une lectrice analytique, qui connaît les allées et venues de la prose intelligente. Tout cela se reflète dans son écriture. La Robe blanche est le résultat dun immense travail narratif, tant dans la forme que dans le fond. Lintrigue est centrée sur lartiste italienne Pippa Bacca qui, à 33 ans, quitte Milan habillée en mariée et a lintention datteindre Jérusalem en auto-stop, pour sauver le monde. Mais tout se termine tragiquement dans une forêt près dIstanbul.

Le roman se déplace dans ce cadre thématique, structuré à partir de détails ou dindices qui ouvrent des portes ou qui indiquent simplement où diriger la vue. Une tapisserie sur un tableau de Botticelli, accrochée dans la salle à manger, dès le début du roman, semble rester dans le subconscient du lecteur, qui reviendra sur cette scène nuptiale et se souviendra plus clairement de ses détails. A tout cela s'ajoute le cas de sa mère, qui cherche aussi de nombreuses années plus tard, racheter son histoire, venger son passé et trouver les mots précis pour défendre sa cause. Elle et l'artiste italienne montrent leurs robes blanches de mariée, un vêtement qui unit les deux vies d'une manière inattendue. Ainsi, Nathalie Léger, lorsqu'elle nous parle de la vie des autres, nous dit aussi des choses sur elle-même.

Grand roman.14 s Ina Groovie365 241

Dos vestidos blancos se trenzan en el relato (ensayo, biografía e investigación). Una novia performática recorre Europa a dedo con el fin de hablar sobre la bondad. Otra novia, ex novia, madre de la narradora, insiste en conseguir reparación por su historia mientras estuvo casada. Dos vestidos blancos que son paréntesis y encierran a la autora, la acorralan y conminan a contar, asimismo, otras performances femeninas donde el mero hecho de existir es un peligro.

Fantástico tema, extensión justa, preciosas disgregaciones y un aliento para seguir el camino de todas las artistas aquí nombradas. 5 s Justine236 102

The White Dress by Nathalie Léger (tr. Natasha Lehrer) is the final book in her informal trilogy on women artists. Each book is theoretically centered around a female artistthe portraits of the Countess de Castiglione, Barbara Loden and her film Wanda, and Pippa Baccas quest for peace across the Balkans and into the Middle East in a white wedding dress. Each woman and her story have an element of tragedy, some mystery for Léger that draws her to these subjects, that stirs Légers ruminations on art, women artists, society, and finally her personal lifeparticularly her relationship with her mother. As the loose trilogy progresses, her mother becomes more and more of a central figure in these books, in The White Dress, Légers mother and her problems and demands begin to almost invade the narrative. We witness Léger breaking down under the weight of her mothers demands for justice and of her inability to really understand Pippa Bacca for this project, let alone how men have the audacity to not only take control over womens lives, narratives, and art but to steal their gaze. At a certain point, the pressure, a torrent of anger floods the page, and by the end, she is fed up, exhausted, terse Léger drops the final pages into the readers lap and walks away.

4.5*

I cry out that I dont want to, that I have already described it, that Ive never stopped talking about her in my books, that its enough now, I cry out that she has to stop putting her life into the dossier and the dossier into mine, I cry out that it isnt up to me to bring her justice, that her cause is pitiful, that I want to go back to my research.

Not only did I tell her that day about my project, but I remember commenting at length, against a background of grunting, yowling, and cackling that bore down over our heads, talking about my heartbreaking inability to understand this girls story, my inability to grasp what was simultaneously significant and trivial in her gesture, and probably beyond comprehension.

4 s Cherise WolasAuthor 4 books278

The third and last in this loose trilogy where the narrator inquires into the lives of women she's become interested in through her research work as a curator. With elements of biography, criticism, memoir and fiction, they are also slim books of personal exploration, with the author using her subjects' stories to interrogate aspects of her own, including her memories of her father's extramarital affair when she was a child, her parents' bitter divorce, and her mother's yearning for justice, for her side of the story to be told. The women who are the focus of these books, the author's mother, are similar in that they are not straightforward and strong feminist heroes, but instead struggled with their own sense of being. In the first, Exposition, the woman at issue is the Countess of Castiglone, the most photographed woman in 19th century Paris; in Suite for Barbara Loden, it's the American actress and filmmaker Loden who directed and played the title role in the 1970s arthouse movie Wanda; and in The White Dress, it is the young Italian performance artist, Pippa Bacca, who in 2008 set out to hitchhike from Milan to Jerusalem wearing a customized white wedding dress. Each of these books is quite different, each compelling.2021-reading-challenge books-in-translation french-writers3 s Tonymess465 42

Outstanding, intricate but deft, personal but detached, masterful writing, didnt think Nathalie Léger could better Suite for Barbara Loden but she has.

Yet again a perfect book from Dorothy A Publishing Project, Ive yet to come across anything other than top shelf works from them.3 s Alena KharchankaAuthor 3 books187

Nathalie conoce la historia de Pippa Bacca, una arista que realiza una performance: viaja haciendo autostop, vestida de novia, de blanco, es su forma de pedir la paz en los países que han estado en guerra en los últimos años. Lo hace así, de coche en coche, para mostrar al mundo que se puede confiar en el prójimo.

?

Desaparece el 31 de marzo de 2008. La encuentran violada y asesinada, un par de semanas después.

?

Este hecho horrible, trágico e indescriptible es lo que hace que Nathalie empiece a reflexionar sobre el papel del arte, del performance, de la mujer en el mundo. Poco a poco, como suele suceder en los libros de Léger, empieza a tejerse una historia paralela, la de su madre y su infeliz e injusto matrimonio, que pide (no, más bien exige) la venganza: «Podrías actuar por mí, podrías hablar por mí, podrías defenderme y hasta vengarme».

?

En apenas 90 páginas Nathalie ha sido capaz de contar tanto, de reflexionar de tal manera, que to me quedo sin palabras. Me asombra su capacidad de desarrollar una historia a través de una otra, y todas las historias que transparentan dentro de esas dos.

?

Nos habla de los padres ausentes (« todas esas generaciones de padres irritados, malhumorados o ansiosos, que no pegan o no pegan demasiado »), de madres infelices, del vestido de novia como símbolo, también como cárcel. Nos habla del arte, de artistas, de su propia incomprensión de sus obras y sus performance. También de la venganza, del peso de convivir con tus traumas heredadas. Y de la pregunta que no te abandona jamas:

?

«A veces, en estos momentos vacíos, cuando la mente no está ocupada con ningún problema ni ningún placer, cuando ningún tema se impone, ni por obligación, ni siquiera por distracción, cuando con mirar ya no alcanza y no hacer nada es imposible, hay que volver a una de las preguntas que se guardan aparte, sin respuesta, en un cuarto reservado para ellas solas; encendemos la luz, la pregunta está ahí, minúscula, esperando».

(Ahora bien, las traducciones de Chai y de Sexto Piso parecen libros distintos. Lo leí en versión argentina y es una delicia. Y sin embargo la versión española parece otro libro).3 s DawnAuthor 4 books42

A lucid and often devastating investment in performance - while trying to commemorate Pippa Baccas last performance project and murder, the writer veers toward her mothers struggle to reclaim justice after a humiliating marriage and divorce. Revolving around the wedding dress, the passages start loose and continually tighten into a pretty magnificent experience of motherhood, daughterhood, wifehood... 3 s Esther554 23

Ñi, no me ha entusiasmado. Está muy bonito entrelazado el ensayo, pero me hubiera gustado más que se centrara en el caso de Pippa y menos en otras cuestiones.

Partiendo de la base del vestido blanco casi como un personaje más , Léger parte de un vínculo entre distintas mujeres. Este trabajo me parece estupendo peeeeeero no era lo que esperaba encontrar. Éste es sin duda el hilo central y no el caso de Pippa Bacca.3 s Bart Van Overmeire286 56

Interesting book, covering both the story of Pippa Bacca and that of the author and her mother.owned-books read-2021 read-in-english ...more3 s Vivian77

I dont think Im smart enough to know everything that was going on in this book but still found it heavy and a bit funny. Id be in trouble if I aired my moms dirty laundry the author did3 s Violely327 109

Una artista que se pone un vestido de novia y quiere viajar desde Milán hasta Jerusalén a dedo y vestida así. La pauta que se pone a sí misma de no decirle que no a ninguno de los vehículos que se paren para llevarla, porque parte de su performance incluía la confianza en el otro. El encuentro con la muerte, de una forma atroz. ¿El descubrimiento de la maldad humana?, este libro habla de utopías, de arte y variadas performance hechas por mujeres artistas, de lo que estos experimentos muestran de la sociedad y las mujeres, de lo que el otro se cree en derecho de hacer con nuestros cuerpos, con nuestras vidas, con todas nosotras, como un objeto del uso, deseo, abuso y descarte.

Léger va hilando en la historia de la artista Pippa Bacca otras historias de mujeres artistas, del lugar que representan sus obras, de lo que hicieron y los resultados que tuvieron. Entre ellas rescato la de Marina Abramovic y su Rhythm 0, performance en la que dejó a disposición del público 72 objetos para que cada uno de los visitantes pueda usar con ella de la forma que quiera. (...) el público le arrancó la ropa, le clavó espinas en la carne, le tajeó el cuello con una navaja, bebió su sangre, la ató con cadenas, la golpeó con correas, la amenazó con un revólver (47). (...) En medio de la noche, un hombre cargó la pistola y la apoyó contra la nuca de la artista, algunos se opusieron, otros sencillamente dijeron que esa era la idea, que el revólver estaba para usarlo, que ella se lo había buscado, (...) y entonces entró el galerista para anunciar que ya habían pasado las seis horas y la performance había llegado a su fin, Abramovic se levantó, caminó entre el público, que se apartó sin decir una sola palabra, sorprendido, según contó ella, de verla viva: ah, así que no era un objeto, era una mujer eso pensaron, dijo (...).

Somos mujeres, aunque muchas veces (muchas) se piensa que somos objetos. 2 s fdifrantumaglia189 50

Vivere intensamente, buttarsi nel mondo per raccontare, esistere in nome della sorellanza. Come ci ricorda Nathalie Léger, facendo cenno tra le altre cose nellAbito bianco anche alle tantissime testimonianze di donne che unaltra autrice, Svjatlana Aleksievi?, usa per raccontare la guerra: più che una storia appunto di guerra, stava tramandando una storia dei sentimenti espressi nella loro voce originaria. Ed è quello che voleva fare Pippa Bacca con la sua performance.

Leggi la recensione completa: http://www.lindiependente.it/per-pipp...3 s Anita522

Nathalie Léger logra en un libro muy breve, hablar del arte de performance, de la violencia contra las mujeres y de cómo conciliar el arte en un mundo plagado de violencia. Creo que nadie escribe sobre el arte como ella. 2 s Elena Monti95 89

Lotto marzo 2008 lartista milanese Pippa Bacca inizia un viaggio dal valore simbolico: con indosso un abito da sposa, parte da Milano diretta a Gerusalemme. Lo scopo è portare un messaggio di pace attraversando in autostop paesi e regioni martoriati dalla guerra. La performance viene documentata con foto e brevi video, fino al tragico epilogo in Turchia, quando lartista viene violentata e uccisa da un camionista che le aveva offerto un passaggio.

Nathalie Léger decide di raccontare la storia di Pippa Bacca, partendo dal suo viaggio verso Milano per intervistare la madre dellartista. Intervista che non verrà portata a compimento per la difficoltà di porsi di fronte al dolore di una madre a cui è stata brutalmente uccisa la figlia, come conseguenza di una performance artistica.

Un tema già trattato da Marina Abramovic in Rhythm 0, del 1974, in cui il pubblico le strappò i vestiti, le affondò delle spine nella carne, le legò la gola con il rasoio, bevve il suo sangue, la colpì con delle cinghie, la minacciò con una pistola. La stessa Marina al termine della performance ha detto parole che oggi suonano come una profezia: La lezione che ho imparato da questa esperienza è che nelle nostre performance possiamo spingerci lontanissimo, ma se lasciamo fare al pubblico, possiamo restare uccisi.

Labito bianco però è un libro che ricorda quasi un memoir. Protagonista silenziosa della storia è la madre dellautrice, donna ormai vedova che chiede alla figlia di renderle giustizia e denunciare le violenze domestiche a cui per anni è stata sottoposta.

Ho letto in Balzac, una donna abbandonata ha un che dimponente e di sacro [ ] è linnocenza seduta sui detriti di tutte le virtù morte. [ ] Non ricordo niente che sia stato imponente o sacro, nessuna virtù ma una figura umiliata, fatta a pezzi, sempre in lacrime. Non ho sempre amato mia madre. Era schierata con i perdenti ed ero disgustata dal suo fazzolettino sempre umido, allepoca non ero capace di abbracciarla, di consolarla, era schiacciata nellumiliazione di essere stata abbandonata, il terrore di ritrovarsi sola con quattro figli, senza soldi, senza lavoro, soprattutto senza forze, niente.femminismi3 s Delia RaineyAuthor 2 books42

seriously. no one does it nathalie leger. this book goes towards emotional honesty and depths, creating a piece of art to ask questions of art and the torment of creation. leger is obsessed with her research on a woman artist who didn't make it through her life's work ~ the artist set off to run through different countries in a wedding dress, to promote devotion to world peace. this researcher, or narrator, invites us also to sit with her on a couch as she navigates her mother's grief of the 1970s which pours into present day, when her husband (the narrator's father) cheats on her and wins the divorce court case. the only proof of this humiliation remains in a dossier of papers, which, in an act similar to performance art, must be documented by the narrator, her daughter, a writer, as "revenge" or "justice". there is that argument about the woman traveler in the wedding dress, who was murdered, that she "deserved it" or "had it coming" and this sentiment is commonly said of tragedies that women face, no matter how much they were kind, prepared, and wanting "goodness". leger puts evidence to scale of other woman artists, such as yoko ono, marina abromovic, carolee schneemann, providing a conversation on how many view violence against women as inevitable, or "part of the art", but it's not. i think about the narrator, leger, wanting to speak to the artist's mother about her death, as journalist, asking for her grief in order to re-appropriate it for art, and then she backs out, taking the train back almost immediately upon touching ground in milan. oh, am i describing too much? reading this book, finishing it, i just want to write. i want to write in long, run-on sentences full of lyrical beauty and confusion. this kind of reading experience is rare. leger acts as an archivist for her mother's pain and the artist's death, in order to find out something, or to move on. it's cinematic as much as it's essayistic, collaging these two "narratives" of women wanting. wanting what? of course, to live. 1 Marc842 124

Until probably my 40s, I'd been somewhat dismissive of performance art. I was guilty of overlooking its ability to reframe everything. The WHAT and WHY are immediately brought to the fore and one's place in space and time are questioned. Or, put more succinctly by Léger, "Whether or not you understand them, you have to take even the most outlandish gestures seriously." Sometimes, in those empty moments when the mind isn't taken up by worry or pleasure, when no single thing is calling for attention, no obligation or even distraction, when observing is no longer enough and doing nothing is impossible, you must return to one of those unanswered questions, in a room off to one side, you switch on the light and the question is poised there, waiting. In 2008, the Italian performance artist Pippa Bacca set out in a wedding dress to (hitch)hike from Italy to the Middle East in order to promote world peace. Tragically and ironically, she was murdered. Léger explores this project in her characteristic blend of autobiography, biography, and philosophic inquiry examining mother-daughter relationships, marriage, art, and the inherent danger of being a woman. During one of her stops along the way a local journalist asked [Pippa]: "Why hitchhike?" She replied: "It's a way of showing trust toward your fellow human beings. To prove that when you show trust you receive nothing but goodness." ... Pippa Bacca's idea was also that she would never refuse to get in a car. This was not just an idea, it was the inexorable principle of her project, the inexorable principle of its existence, to welcome, to trust. This trust is what leads to Bacca's death and yet Léger avoids simple conclusions and reactionary judgments while still acknowledging the dangers of testing such principles.

The last in Léger's triptych, this book is painful, thought-provoking, and carefully considered.nonfiction owned publisher_dorothy ...more2 s Nadia71 4

Quizás puede ser porque esto es una especie de trilogía, y yo solo leí el último. Pero este libro me sorprendió para bien y para mal. Buscaba algo medianamente liviano que aliviara la pena de haber terminado un libro que amé, pero terminé encontrándome con una historia muy profunda, triste y difusa.

Los límites entre la historia de Pippa Bacca y la madre de la autora se desdibujan constantemente y hacia el final, Pippa es solo una actriz secundaria en una triste y ya conocida historia familiar.

El verdadero tema de este libro es el vínculo madre/hija, inesperado, y doloroso, está muy bien descrito y toca nervios de manera sencilla y orgánica.

En resumen, es un lindo libro...pero no lo que esperaba.2 s Emilia514 123

Al saber la historia, partí con rabia el libro y terminé más enchuchada con las últimas páginas. Encuentro que la historia era inmensa y que no era necesario mezclarla con lo de la mamá (o tal vez la historia era la de la mamá y la otra se mezcló). No caché muy bien cuál era el nexo a pesar del vestido.2 s Alejandro Koppmann58

Otro texto inclasificable de Nathalie Leger.

Entre reportaje, reflexión personal , autobiografía y novela.

Al igual que con Barbara Loden la autora encuentra en la historia de la artista Pippa Bacca otra manera de insistir en que miremos lo qué pasa frente a nuestros ojos. 2 s sydney20 5

a 2020 favorite for sure. will be thinking about this one for a long time. 2 s Mar13

Por lo general las primeras treinta páginas de un libro cuestan. Bueno, a ver, ¿quiénes son los personajes? ¿Qué quieren? ¿Qué les pasa? ¿Cuál es el objetivo de este libro? Nathalie Léger escribe un libro con extensas oraciones, complejísimas, completísimas, llenas de contenido, analogías, diálogos, reflexiones, dividido en parráfos. Es evidente entonces, que me costó entrar en ritmo con esas primeras treinta páginas, más siendo mi primera vez leyendo a la autora. La cuestión con libros tan cortos es que, estas primeras treinta páginas, son casi la mitad del libro. Llegada a esa mitad del libro, me estaba gustando mucho lo que leía, me parecía muy interesante, pero no encontraba aún la unión de todos estos relatos, provocando una leve distancia con Léger. Eso fue ayer. Hoy, me senté con la intención de avanzar un poco más antes de almorzar. Digamos que ya simplemente no me importa almorzar, sólo hablar de este libro. Leía un poco, marcaba alguna parte y leía otro poco, hasta que llegué a las últimas treinta páginas. Hasta entonces tenía un poco de sueño, me costaba concentrarme. Pero esas útimas páginas me despertaron con una violencia fascinante. Me consumieron en una lectura frénetica en la que incluso el tiempo en que frenaba a remarcar párrafos enteros me resultaba insoportable. Qué maravila, por favor. En realidad, mi reacción al terminar fue "qué terrible". Leí esas últimas frases y me quedé pasando hojas invisibles esperando más. Que terrible lo que me hizo este libro, qué terrible lo que relata, qué terrible la escritura de Nathalie Léger, qué terrible. Empecé esperando leer una especie de road trip sobre una mujer con un vestido de novia viajando por Europa, y me encontré con un viaje sobre mujeres del mundo, de todos los tiempos. Empezando por el hecho de que me encantó darme cuenta de que su narradora es Nathalie, relatando su realidad durante la investigación, y que no es un relato ficcional, terminando con el fascinante hilado de vértices que culminó en ese final desgarrador. Mis pensamientos en este momento están tan desordenados como los de la autora al iniciar este trayecto, lo único claro es mi fascinación. Su reflexión sobre las perfomances, sobre por qué y para qué existen, es refrescante y me hizo replantearme todo lo que aprendí en Estética en la Facultad. Su reflexión sobre la literatura, sobre para qué y por qué existe. ¿Por qué escribimos? ¿Por qué escribo esta reseña?. "¿Para qué crees que escribes si no es para hacer justicia?". El dolor de su madre, la reconciliación que tiene con su historia gracias a la resignificación que le da su hija a la misma. Ojalá pudiera volver a sentir lo que sentí cuando leí, "(...) hay algo que también puedo hacer: puedo ponerme el vestido de novia y limpiar la acera del tribunal de Grasse". Ahí entendí todo, ahí dije, "si, para eso existe el arte." .

Probablemente siga encontrando cosas fascinantes en esta lectura en los próximos días; probablemente durante toda mi vida.el-clú1 actuallymynamesssantiago258 198

"Les dije: tanto si lo suyo fue un fracaso o un éxito, en cualquier caso murió por eso".

Pls, la amo a Léger. Not ella volcando todos sus traumas familiares mientras narra a Pippa Bacca.

Tenemos los mismos mecanismos de pensamiento, digresivos, abstractos, es muy lindo verlo solidificado en lenguaje. La historización que hace del arte de performance es genial. Voy a hacer una digresión para decir que estoy escuchando al vecino de enfrente que me parece cool y siempre me ve leyendo en la terraza hablando con un amigo suyo sobre clínicas de guiones y del Di Tella como lugar de artistas en los 60's; eso confirma mi teoría de que se dedica/le interesa algo cercano al arte, ojalá se haga mi amigo, aunque me debe llevar como 10 años; how big how blue how beautiful. Volviendo a Nathalie, la mezcla autobiografía/investigación que hizo a partir de Barbara Loden me pareció muy cool, porque ella misma se desprendía de la investigación y ahí daba lugar a su propia vida. En cambio acá siento que se narró a sí misma y a su mamá porque sí. Ni entra a hablar de Pippa que ya está contando que los papás se peleaban jsjdjsja. Y no lo cuenta de una forma muy atractiva, pareciera más bien una charla extremadamente solemne, densa con un amigo. Es lo que a veces le pasa a Barthes, son personas que saben mucho y da placer leerlas pero no tienen la ¿humanidad-popularidad-cercanía con la tierra? suficiente como para tener conciencia del texto y sacarle el máximo provecho. En otras palabras, cabezas críticas. Un poco siento que quiso lucrar haciendo algo similar a lo de Loden. En fin, lo último, al inicio y en la contratapa dice que Léger conoció el proyecto de Pippa en 2008, pero en los agradecimientos dice que la conoció con un documental de 2012, lo dejo a tu criterio

Autor del comentario:

=================================